The Devil’s in the details, as the saying goes. I was recently contemplating the new saw that cell phones remove, like, 90% of plot devices from modern stories because so many plots, especially in horror/sci-fi stories, depend on characters being out of communication with the rest of humanity – not to mention that Internet connectivity on the move would make researching things on the fly frickin’ simple. Now, I don’t actually believe that cell phones and other new communication/information technology makes plotting difficult – there’s this thing called creativity, you see – but it’s an interesting game to play, taking any old movie that depends on isolation, miscommunication, or lack of information, drop a smart phone into it, and see how minutes you get into the plot before the movie just ends peacefully.

The Devil’s in the details, as the saying goes. I was recently contemplating the new saw that cell phones remove, like, 90% of plot devices from modern stories because so many plots, especially in horror/sci-fi stories, depend on characters being out of communication with the rest of humanity – not to mention that Internet connectivity on the move would make researching things on the fly frickin’ simple. Now, I don’t actually believe that cell phones and other new communication/information technology makes plotting difficult – there’s this thing called creativity, you see – but it’s an interesting game to play, taking any old movie that depends on isolation, miscommunication, or lack of information, drop a smart phone into it, and see how minutes you get into the plot before the movie just ends peacefully.

What it really got me thinking about, though, was the Dangers of Specificity when you’re writing. This is true for all writing, but especially true for SF/F writing, because when you’re writing about demons or zombies or aliens or time travel devices, you strive for complete realism and verisimilitude in the details of your story to ground the fantastic in the real. If your protagonist is fleeing demonic hordes, having them run into a Burger King for shelter instead of some fake, made-up fast food chain will instantly make the scene a little easier to accept by your readers. Of course, the details in the actual writing – what the place smells like, what kind of customers are there at 11PM, the music being played, the attitude of the workers behind the counter – will have a much larger impact. But pop-culture references and up-to-date cultural details will help, and they’re often a shorthand.

The problem with up-to-date references, of course, is that they age badly.

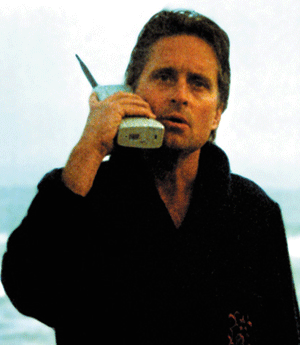

Ignoring pop-culture, which I’ve discussed before, let’s consider the simple fact that while details are your friend, they often turn evil and bite you in the writing ass. Consider the image I’ve got here: Gordon Gecko from 1987’s Wall Street. Not only did that movie star a pre-Cocaine bloat Charlie Sheen, it also apparently starred the World’s Largest Cell Phone. That’s a great detail: At the time, it conveyed to the audience Gecko’s wealth and power with a nifty detail, because in 1987 not everyone had a cell phone. They were icons of, well, wealth and power.

Today, of course, the universe has been cruel to Oliver Stone and Gecko’s huge, bulky cell phone is so amusing to us it’s actually a sight gag in the trailer for Wall Street 2: Wall Streeter. No, really, check it (about 27 seconds in). That’s how details kill you. Burger King might be the perfect detail today, but what about 20 years from now? Stanley Kubrick thought TWA was going to last for centuries. The more specific you are, the more danger your story is in.

On the other hand, I’ve read stories and novels from 100 years ago that still work just fine because they lack that sort of specificity. You can read a short story by F. Scott Fitzgerald and despite the fact that it was published in 1922 or so, it reads just fine, because his details are elastic. There are automobiles, telephones, airplanes – but no specific models or types. Yes, it’s still a bit dated, but as a whole it will work just fine. Or take a current story like Avatar: Not the greatest story ever told by a long shot, and way, wayyyy over overrated, but one thing it has going for it is a complete lack of specificity. Not within its own universe, which is realized with a great amount of detail, but concerning the world from which the story springs – namely a future-earth. We get absolutely nothing about things at home from this movie. No corporate shout-outs, no technological/cultural changes. Nothing. It’s a blank slate and thus the story lives entirely, purely within the alien landscape constructed for it, and as a result as long as we’re not sending Space Marines to fight corporate wars against blue-skinned natives on foreign planets, the movie will remain firmly science-fictional. The lack of grounding details works well for it. There’s no big TWA logo anywhere to distract future audiences from the story.

Well, the world is dumping what appears to be six hundred feet of snow on my house right now, so I have to wrap this up and go outside to move tons of crystallized water from my sidewalk. Wish me luck. The longer I live in the northeast USA the more certain I am that my demise will come after drinking four Hot Toddies and then shoveling snow for an hour.

I find this to be an interesting topic. Especially when I think of authors like Stephen King who liberally pepper their work with pop culture references and icons. Those stories definitely feel real because of that — which aids in bringing the horror home to the reader — but in fifty or a hundred years will all of that specificity make King’s thrillers seem quaint?

Related to this, I noticed in the Avery Cates books that you steer away from using specific locations. For instance when they’re in Paris you never quite pin down where they are beyond noting the Seine (although you don’t name it). At first I thought it would make the scene more generic, but really it worked cleverly to allow me to continue imagining Avery’s world in the way that I’d begun in the first pages. You gave just enough detail to place us, but left us to fill in the specifics. Anyway, I liked that choice and I’ll probably use it someday in my own writing.

Jeff – It is an interesting point you bring up because I sometimes feel that the very specificity you talk about can sometimes be a good thing. I am thinking about when I look at old photos from my childhood, I find the little details in the background, and they really bring the exact place and time to life.

I also love films shot in NYC in the 70s and 80s, so much transformation has taken place that I yearn to see what this yester-year looked like: the differences, the similarities.

Sure, TWA isn’t around anymore, but is it such a bad thing that a far-distant viewer/reader may have to wonder, or actually look up on his computer device of the future, just what exactly TWA was?

It can be a double-edged sword. I think both techniques work, and this is an important decision every writer has to make.

Great topic-

Tricia,

Thanks for the comment re: The Cates books. I figure since they’re from Cates’ POV, he himself doesn’t really know place names, or what buildings are. I mean, why in the world would Cates know what Notre Dame looks like? Or have even heard of Notre Dame in the first place? So when he gets to France, he sees a big, fancy building. I try to give enough detail so people who know a place can pick out the details, but I also try to stay in line with what Cates should know.

J

Jay,

You’re right, of course–it has its strengths too, and you can use it as a tool to achieve a specific purpose. I tend to shy away from it in my own work, and that shows when I bloviate about it. But you’re absolutely right–there is wonder in those old crumbly details, too.

J

Jeff, that makes perfect sense and I feel kind of dumb now for not thinking of that.

By the way it’s 61 degrees here in Vegas. Not that I’m rubbing it in or anything 😉

I’m thinking through classic books, and the landscape is totally different, like you say. In, say, pre-1950’s books, is the absence of specific references due to the fact that the author refrained from making them, or because there were no such references to make? I think for older classics it’s really the difference of – a culture without aggressive marketing and big chains/corporations vs. what we have today.

Of course I agree with what you’re saying about 1980’s movies, etc. Even cell phones from 5 years ago look huge.

I wonder how many authors that are writing now care about the longevity of their work. It’s a disposable world.

Elisabeth,

Well, damn, *I* care. I want my books to form the basis for the new society after the bomb drops. Disposable? My god. I want future generations to build huge statues of me with plaques at the bottom that read WRITER BEST EVER or similar.

J

Interesting post! I tend to shy away from such specifics in scenes set in the present, but use them on scenes set in the past. The thing about the books I’m writing now is, they’re pretty much doomed to be dated. My MC is a genealogist and the mysteries have ties to the past, so that the present always has to be a set number of years after some historic event, like the Civil War or the post-WWI flu epidemic.

So I use the specifics to evoke certain periods, but in the “present” scenes I avoid them because I don’t want readers of the future to be distracted from the story by weird details.

Another example of what you’re talking about would be one of the early “In Death” books that Nora Roberts writes under the psudonymn J.D. Robb. In one of the books written pre- 9/11 she has something happen at the Twin Towers. (Of course, she also keeps having her MC take “boiling” showers at 101 degrees Fahrenheit, which is less than three degrees warmer than *sweat* but . . . grrr.)

Most writers care. Part of loving books is having an understanding of the value of longevity. But SOME probably don’t care, which is sort of terrible.

This is what I meant to say, but I see that I expressed the exact opposite.

If anyone’s writing can give us hope after the nuclear holocaust, it’s yours.

I want you to know I came straight over here to comment last night because the pic in your post made me crack up laughing as soon as I saw it.

In a related example, some friends and I are playing in a conspiracy-theory, X-file-ish, type role-playing game. (Using the Alternity System, for those of you who are nerdy enough to want to know.) We discussed the cell-phone/internet problem which we had run into while playing in other modern-day settings, and, because of that, decided to set the game in 1967.

Sometimes dating a story is not such a bad thing. I think with Wall street Oliver Stone was making a statement about the 80’s culture of greed. In doing that, it was important to highlight that culture and the visual aspects of that culture, whereas if he were making a timeless story about greed he may have chosen different props or settings.

Specifics clearly hurt science fiction because you are in essence making predictions. Science fiction stories are not trying to paint of picture of a specific time frame and are instead trying to make a future that is possible (though not always plausible).

When dealing with the present it is better to deal with it as a specific time frame, and not deal with it as ‘the present’. That way viewers have a frame of reference and are not as easily distracted. The pop icons become things that add texture to the story as apposed to things that distract.

If you are interested to see how cell phones would affect movies check out College Humors video on just that topic. http://www.collegehumor.com/video:1832002

Ami, That’s interesting – I never thought about this in the zone of games et al. But of course games have a plot, too, albeit a shared and malleable one. Thanks for the example!

Hi Travis, I see your point re: SF Vs. non-SF and time-frame. But I’m not sure it’s ever better to have a specific time frame, unless that is indeed part of the point of your story. I always prefer to go for “timeless” in regards to setting if the themes of my story are also timeless. But then, your mileage may vary and sometimes a “timeless” setting just feels empty and undetailed.