A Million Ways to Fail

How I Feel Most Saturday Mornings.

One of the most awesome things about writing has to be the almost infinite chances it offers you to fail.

Even if we stick to the slim piece of reality that mortal minds can comprehend, we have quite a list:

- First, you can fail to even start writing that idea you have. It’s a nice, clean failure, but a failure nonetheless.

- Then, of course, you can fail to finish it. I estimate I’ve failed in this manner about 5,000 times. That’s a conservative estimate.

- Or you can finish it and then fail to do anything with the raw material.

- You can fail to heed feedback, advice, or proofreading marks.

- You can fail to show it around or submit it or make any other attempt to sell the piece or at least have it be read.

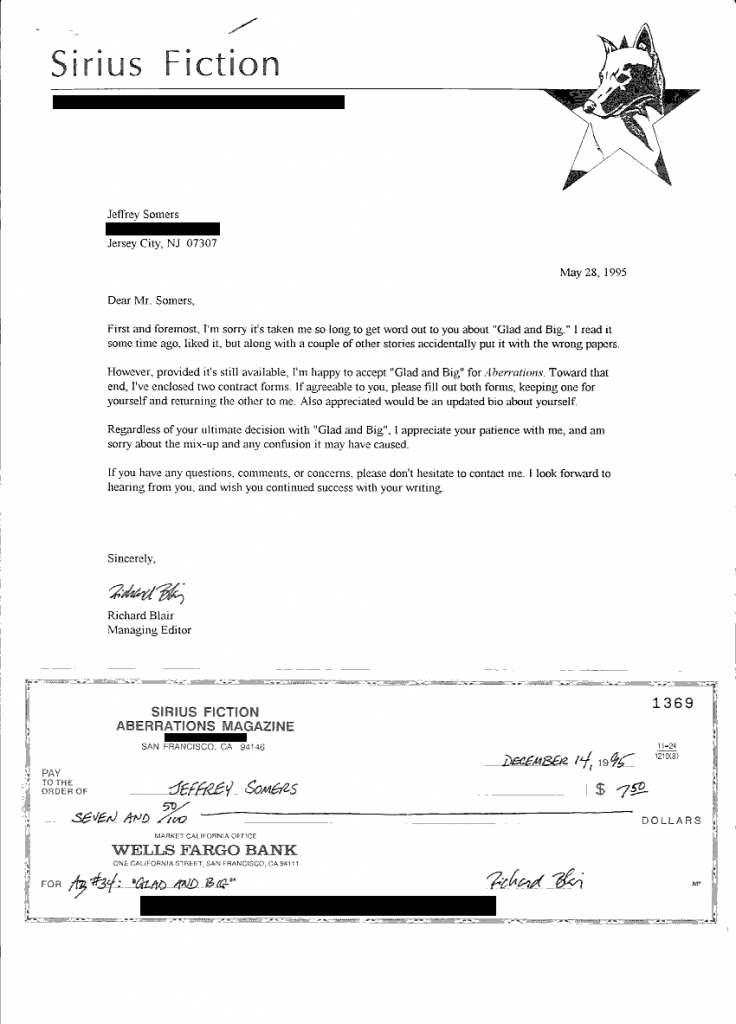

- You can submit it, and fail to sell it. And fail and fail and fail to sell it.

- You can sell it, and then fail to, you know, sell it.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the glorious future world we find ourselves in offers even more ways to fail, in terms of promotion and social media. So now you can not only fail to write something, or fail to finish something, or fail to sell it, but you can also fail to be interesting or clever enough on Twitter. The failure involved in writing just one novel is monumental.

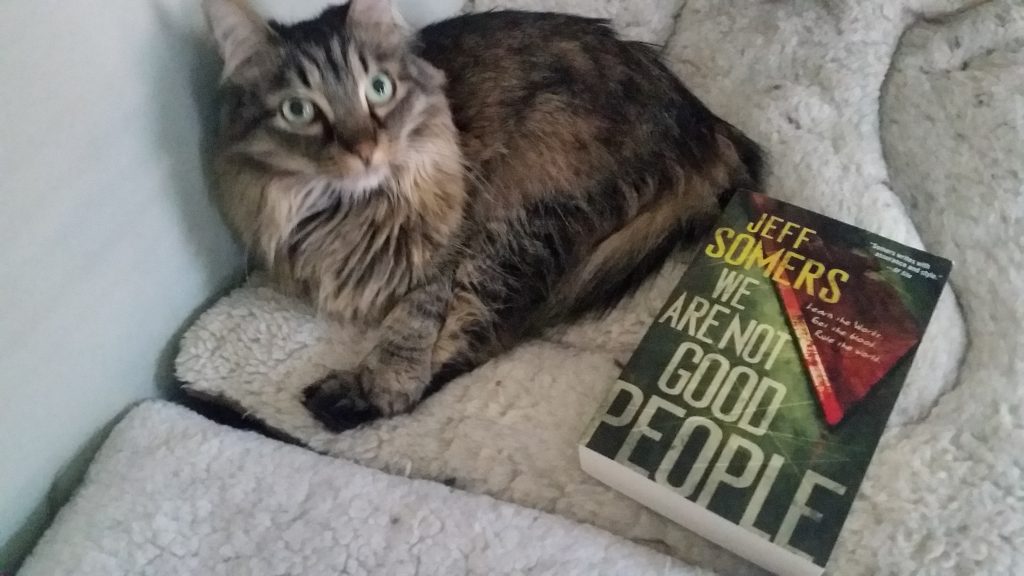

And you wonder why writers drink and talk to cats. Well, why they drink more and talk back to cats, anyway.

The worst part, of course, is that most of the time this kind of failure is necessary in order to write anything and then get it out there. In one of Douglas Adams’ Hitchhiker books, he has a thing about people learning to fly in which he describes it as throwing yourself at the ground, then distracting yourself at the very last possible moment so that you forget to hit it. And that’s writing, sometimes, most times: Throwing yourself at a mountain of failure and then, somehow, distracting yourself from hitting it at the last possible moment and sailing over.

And how do I distract myself from Mount Failure? You guessed it: Whiskey. And cats.

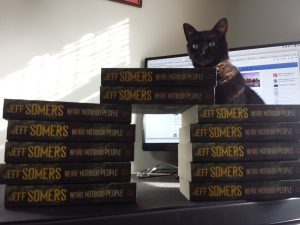

BOOM

BOOK FORT FTW

Well, it sure didn’t take long for my Weekly Recap feature on this here blog to go the way of most of my ideas: Sailing serenely into incompetence. Instead of a Weekly Recap, this has been more of a Whenever I Am Sober at 5PM on a Friday Recap.

Well, it sure didn’t take long for my Weekly Recap feature on this here blog to go the way of most of my ideas: Sailing serenely into incompetence. Instead of a Weekly Recap, this has been more of a Whenever I Am Sober at 5PM on a Friday Recap.