Breakin’ the Law (in D&D)

FRIENDS, I have never claimed to be cool. I was a portly kid with thick glasses, and so I was doomed to be the mascot of every class (spiced with occasional good old-fashioned bullying) until I hit college, when somehow my combination of sarcasm, bad hair, and even thicker glasses alchemically made me, if not cool, at least not uncool. Still, despite my chronic uncoolness at every stop along my journey through life I’ve managed to do two things: Have a lot of fun and toss all the rulebooks out the window.

Now, I don’t mean to imply that I’m some sort of brilliant iconoclast or rebel. Far from it; I’m the sort of guy who gets mildly upset if I don’t get my coffee at the same exact time every day, because what this world needs is MORE ORDER; in other words, I love following rules in general. But I am that classic jackass who looks at a book of rules and thinks, jeez, that’s a lot to read and so I don’t read them and I just sort of wing it and make shit up as I go. This is why all my Ikea furniture looks like torture devices from Isengard, and why I spent six years lost in Canada, refusing to read a map. Yes, I’m that jackass.

A Level 35 Demigod

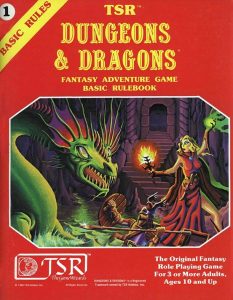

12-year Old Jeff Said HOLY CRAP ITS GOT A DRAGON ON IT, DUNNIT!

Back in my grammar school days I played a bit of Dungeons & Dragons, although I’ll admit I only glanced at the rules. I probably read the Basic Module, or mostly read it, but as we got deeper and deeper in I could never be bothered to read the more advanced rules. D&D had a pretty neat system there, starting off simple and then adding in layers of complexity, but this seemed an awful lot like work, so my friends and I just sort of absorbed the basic concept and then set about just making up whatever we wanted.

Since we were nearing full-on puberty, there were a number of pornographic adventures involving lots of lusty barmaids, witches, and female monsters. Things got … weird. After things got weird, we went full-on acquisitive; the rules for D&D were painfully slow. You started off with nothing, a Level One Thief or Elf or what have you, and you were supposed to slowly make your way through adventures where you would slowly gain experience and level up and slowly discover magic items that would augment your abilities and slowly, slowly, slowly.

One advantage to not reading any rules was the ease with which you could simply decide fuck that, let’s become demigods. So we did.

Acting as Dungeon Masters, we created adventures specifically designed to level up our characters as quickly as possible. We awarded experience points like candy, we littered the adventure with spectacular items gleamed from the Dungeon Master’s Handbook from the Advanced version of the game, and by the end of it we had characters who could basically do anything.

Look on My Works, Ye Mighty

Of course, the game was ruined. Once you have a demigod for a character all you can do is pit them against each other, rolling the dice to see whose obscure and ultra-powerful spell would shatter whose ancient magical shield. That didn’t matter, for me it was a teachable moment, because I realized something very important about myself: I love stats.

Statistics were why I got interested in D&D in the first place (that and the aforementioned pornographic possibilities of role-playing games), just like stats lured me into baseball fandom. The neat rows of numbers, all meaning something, all representing abilities and achievements—I loved them like children. I could calculate an ERA in my head and I instinctively knew the odds of my fireball spell working, and more than anything else I loved the back of a baseball card where a player’s stats were listed and I loved my D&D character sheets where their stats were all laid out.

The same kids who I played D&D with also played in a computer baseball league with me on our Commodore 64s. Microleague Baseball was a marvel; it ran on stats. It came with pre-compiled teams, but you could enter your own and then manage the team in real time. We played entire seasons, made trades, had playoffs and championships. And it was half numbers, half strategy, and not so different from D&D in some ways, although we didn’t cheat much in Microleague. We cheated a little, of course, but not much.

To this day, I don’t read the manual or work too hard to understand the rules. This is why many video games enrage me and also why the washing machine turns on when I play the radio—who has time to pay attention to electrical codes or wiring diagrams?