Learn from Stuff You Hate

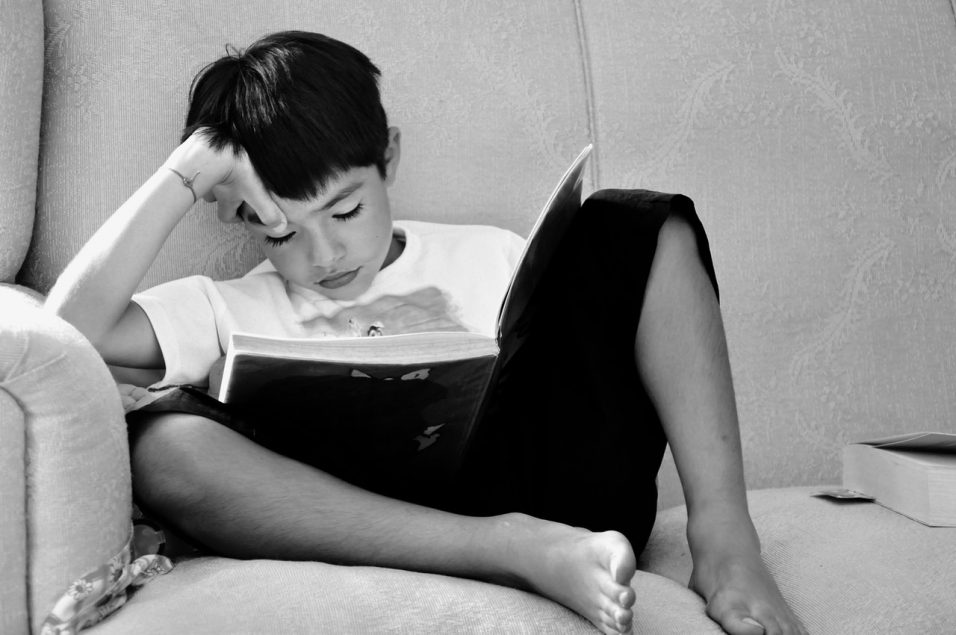

One of the creakiest and most over-offered pieces of writing advice is to “read widely.” Not that it’s bad advice—it isn’t; it’s excellent advice. It’s just that like “show, don’t tell” it’s repeated so often, and so glibly, that many folks in the audience at panels just ignore it. “Read widely” is the “Wild Thing” of amateur guitarists: Everyone knows it, move along, nothing to see here.

The trick to reading widely isn’t to read a lot, or even to read outside your comfortable genres (although, yes to both those things). The real key to how reading widely can help you is to get into Advanced Reading Widely 405, a.k.a. learning good writing stuff from books you don’t actually enjoy.

Not My Books You SOBs

When people “read widely” they usually talk about getting outside their own genre or culture. And yes, if you’re a sci-fi writer, reading thrillers will give you lots of insight into pacing and plot. And if you’re, say, a middle-aged white cis American male who looks good in just about anything, reading books from other cultures and sub-cultures can open your eyes not just to different writing styles and techniques but different points of view that your characters can benefit from.

And that’s all great and necessarily. But the next level is to read books you don’t like, because what you’ll find is that genres and styles you despise have just as much to teach you—and those are lessons you’ll miss if you stay within the admittedly wider bubble of, you know, books you actually enjoy.

This can be true of wildly popular fictions that sell by the truckload but leave you completely baffled as to their appeal: Reverse-engineering that appeal might hold lessons for you, whereas smugly assuming that the millions of people reading those books are morons doesn’t do anything for you or your writing. And if a book is boring the pants off of you that doesn’t mean the author doesn’t pull off an impressive trick with their narrator, or have a dazzling sequence in the middle overflowing with ideas.

At it’s most basic, sometimes reading a terrible book just inspires you to steal the plot and try your own version of it in order to make it, you know, actually interesting (in your opinion).

Of course, reading widely also runs the risk of encountering a book so perfect and amazing you just give up on your own shabby efforts and just walk into the ocean, only to wake up on the beach being resuscitated by the teenage lifeguard and then mocked as you stagger home. Or is that just me?