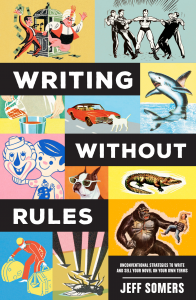

The Clicks

My wife, The Duchess, often gets irritated with me due to my reaction to celebrity sightings. We live near New York City, and are frequently there, so there’s a non-zero chance we’ll run across a famous person. When we do, invariably The Duchess doesn’t notice but I do, and my reaction is to wait about three blocks and then whisper to her that someone famous was hailing a cab or being raptured or something back there. The Duchess curses my name, turns, and races back to see if she can still see them.

My wife, The Duchess, often gets irritated with me due to my reaction to celebrity sightings. We live near New York City, and are frequently there, so there’s a non-zero chance we’ll run across a famous person. When we do, invariably The Duchess doesn’t notice but I do, and my reaction is to wait about three blocks and then whisper to her that someone famous was hailing a cab or being raptured or something back there. The Duchess curses my name, turns, and races back to see if she can still see them.

I do this for three reasons: One, my wife’s rage and antics are amusing to me. Two, I think people are The Worst and thus cannot think of anything worse than strangers intruding on my life. And three, I don’t give a shit about celebrities, and there’s an unreasonable, ornery part of my personality that doesn’t want to feed their famewhore machines with my attention unless they’re performing for me like some sort of court jester or pet monkey.

The Clicks

I carry this attitude to the Internet, where the famewhoriest of famewhores all live. This translates to a truculent refusal to click on things that are very clearly designed to make me click on them—and this goes triple for things that are Outrage Machines, the sort of video or blogger presences that are there to be controversial and upsetting solely so middle aged idiots like me will rush to click on them and see what’s so terrible. So that we can then rush back to our own Internet backwater and write up breathless condemnations, defenses, hot takes, or other reactions. In an attempt to scoop up e second- and third-hand clicks in the wake of the flagship controversy.

The problem with my obstinate refusal to give these folks clicks is that it means I can’t actually see what’s casuing all the fuss.

In the past, if you watched some controversial thing or gave in and listened to something, you could often do so without rewarding the jackass that created it. These days, however, if I click on something just to find out why everyone’s so pissed off, I am in fact rewarding that jackass with a Click. But if I refuse to bestow that Click, then I can’t really judge for myself. It’s a very strange place to be, especially since I myself am out there with my virtual tin cup, begging for Clicks just like everyone else.

Does this mean we’re all living in an episode of Black Mirror? Probably. But as long as I don’t have to fuck any pigs, I’m okay with that.