The Muse

Going back and reading something you created a long time ago is often exciting in the same way playing Russian Roulette can be exciting: You just don’t know how bad it’s gonna be. Sometimes I pull a story or novel from ten years ago and it is truly depressing how awful it is.

Sometimes, of course, the opposite is true. Sometimes you pull out a forgotten draft, and something amazing happens: You’re impressed with yourself. I don’t know about you, but I don’t remember past work very well. I don’t remember anything very well1.

And the thing is, when I’m in the moment writing, I hate everything. All my current work is trash. It’s simplistic and dumb and repeats tricks I did better 20 years ago. But that’s how I always feel, and yet sometimes — sometimes — when I pull out an old piece and re-read it, it turns out to be complex and subtle and hilarious, and I wonder who snuck into my files and dropped this hot piece of great writing, because it couldn’t have been me.

Better with Age

It’s easy to get frustrated, because we always think our current WIP is shit and we had our last good idea seven years ago. But it’s worth remembering that we almost certainly felt that way about our past work when it was in progress. I don’t know how your Muse works, but mine tends to work via manipulation and misdirection, leaving soggy bar napkins in my pockets with strange, obscure phrases and setting things on fire to attract my attention, then refusing to accept the charges on my collect calls when I need bail money. I never feel in control of my creative process, which means I never think anything I’m currently working on — which I can clearly link to myself — is any good, while older work (which I can’t link to myself because I’ve forgotten all the details about its creation) is often surprisingly good, because it was created by a stranger named Past Jeff2.

This is most useful, of course, at that moment when you’re halfway through a project that isn’t working out — or seems like it’s not working out. That moment of despair when you pour yourself three fingers of whiskey and wonder if you’ve ever actually written anything worth reading. At those moments, finding something you wrote and forgot about ten years ago that is actually pretty damn good is the goddamn wind beneath your wings.

Of course, in my case, it’s amazing that I do any good work at all when you consider the sheer number of cats sitting on me at any given time. I can barely breathe, much less write.

Fiction-wise, also not bad. I finished 11 of my monthly short stories, so far (and trust that I will finish #12 in a few days even if I have to kill all the characters in a plane crash). I also finished 4 other stories outside of that monthly exercise. I didn’t complete any novels this year, but I’m 50k words into one and 40k words into a short-story cycle, so I wasn’t napping. I also finished and completed 50k words worth of novella-length parts of the new Avery Cates novel The Burning City and

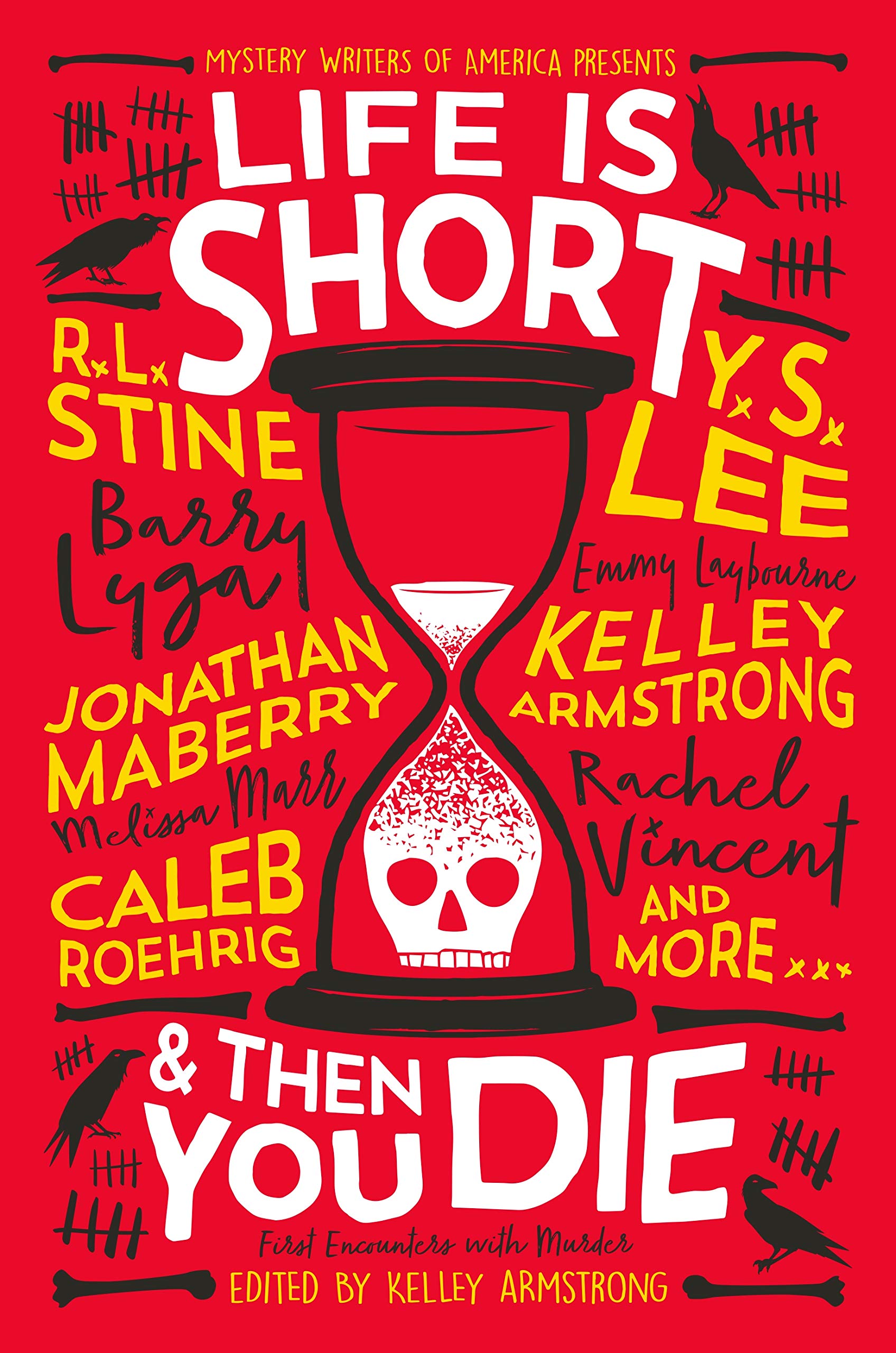

Fiction-wise, also not bad. I finished 11 of my monthly short stories, so far (and trust that I will finish #12 in a few days even if I have to kill all the characters in a plane crash). I also finished 4 other stories outside of that monthly exercise. I didn’t complete any novels this year, but I’m 50k words into one and 40k words into a short-story cycle, so I wasn’t napping. I also finished and completed 50k words worth of novella-length parts of the new Avery Cates novel The Burning City and  I submitted a ton of stories (74, to be exact; note this doesn’t mean 74 separate stories, but 74 submissions of a few stories I currently think are great), as usual, and sold three of them, of which two have published: The Company I Keep in

I submitted a ton of stories (74, to be exact; note this doesn’t mean 74 separate stories, but 74 submissions of a few stories I currently think are great), as usual, and sold three of them, of which two have published: The Company I Keep in  And I started a podcast, like everyone else in this sadly imitative world.

And I started a podcast, like everyone else in this sadly imitative world.