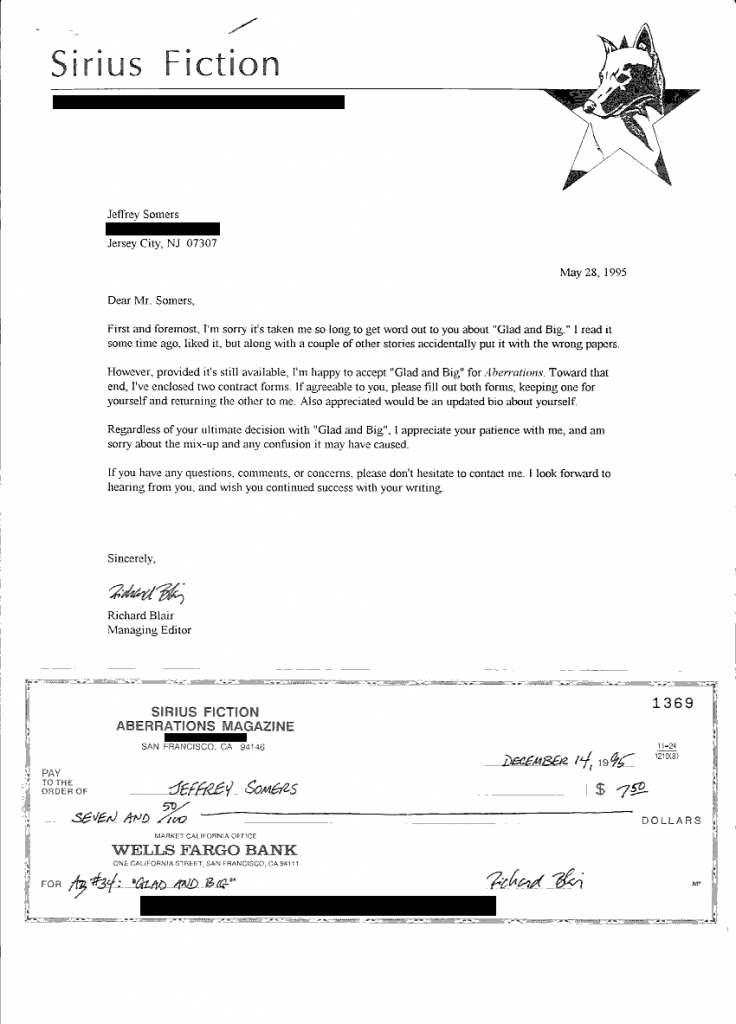

The first short story I ever sold for actual money was Glad and Big, which appeared in Aberrations #34. The sale paid me the princely sum of 1/4 of a penny per word, which worked out to $7.50. That would be nearly twelve dollars in 2016 money, just in case you’re horrified that a writer of my caliber would sell a short story for single-digit monies.

At the time, of course, I was absolutely delighted. I’d had stories appear in zines and other non-paying markets, but this was the first time anyone had actually paid me for one, and naturally I thought of it (and still think of it) as a watershed moment in my career.

I never cashed the check. Part of this was the usual urge to hang onto a momentous thing like my first paycheck for fiction, and yes, part of it was the fact that even in 1995 $7.50 didn’t go far, so it almost wasn’t worth walking to the bank to cash it. Besides, if I’d deposited it, I wouldn’t have it to scan in and post here, now, would I?

Anyways, here’s the story itself. Written more than 20 years ago, I still like it quite a bit.

GLAD AND BIG

Life at Lee’s on second street had a pattern, one I liked well enough. It sucked at my heels with insistent attraction, pulling me back despite the heat and the same old people and the wooden seat worn smooth from years of my weight.

We usually played cards at the small square table in the big bay window, eating Lee’s filling specialties and drinking, smoking cigarettes, and ignoring everyone else. Sometimes I tried to stay away. It never worked. I always needed a drink and the only place to get one was Lee’s and my seat was always open.

That night it was raining and I felt pretty good. The conversation wasn’t too bad and it was warm inside, I was half-tanked all night and I had three packs of cigarettes to get through. Even in a crummy bar and grill like Lee’s, being inside with friends on a rainy night is a special kind of thing. Even being inside with people who drove you crazy like I was was still not bad.

It was an old, run-down place owned by a hundred different people so far, with a truckload of future owners down the line waiting to be suckered. You walked in, the old hardwood floor creaking beneath your feet, and the bar stretched off to your left, far too long, too far into the shadows, built in more optimistic times when booze was cheaper. Tables and the rickety wooden seats they required filled the rest of the floor, never crowded but always occupied.

The walls were three generations of photographs, mostly black and white. They stretched back into the past too far to be remembered; now they were meaningless portraits of people we’d never met, moments in time we couldn’t interpret. They wrapped around the back wall and behind the bar, big and small, some dated and some not. We each had our favorites.

Nelson, the crotchety old bastard, had a soft spot for Helen. She was a brooding, sad-eyed young girl in a bullet bra and a tight, tight turtleneck, sipping coffee, framed by the bay window. She had a Sixties hair-do and in the corner she had written “to Tony – always – Helen.” The steam rising from her coffee, the way she glanced away from the camera. It entranced the old fuck.

Terry liked the one with the big crowd. It was one of the oldest ones, and it showed old Lee’s filled with smiling, jostling, shoving people. There was pandemonium in that picture, static chaos. We all theorized that it had been taken just before a riot, just before the taps ran dry and drove the proles crazy. Terry didn’t have too much chaos in his life, but he desired it. The picture made him feel like it was all at his fingertips.

Me, I like the picture that had to have been the first one there, right behind the bar, framed. It was a dour, lean man wearing a bowler cap and a white apron, leaning behind the bar and staring at the

camera fiercely. A small plaque on the frame declared him “Mr. Lee.” The first owner, I guessed. His name survived but not his memory – if asked I liked to say I thought he’d died in the great tapped keg riots of Terry’s picture. We were the only ones who got it, but then we were the only ones who mattered.

The guy who owned Lee’s now was a middle-aged black man whose life had soured on him somehow. Rilly served us shots and beers with the air of a man confused about his destiny. Confused because it hadn’t turned out the way it was supposed to. He didn’t like us. We sat in his run-down bar and played cards and smoked and stayed drunk and most of our conversation went over his head and I think that’s what really pissed him off. He always lost, walking away to mutter behind his bar about rich white assholes with nothing better to do than take an honest nigger for all he had.

That night he didn’t play, Bobby Hiller sat in, winning and grinning like the two-bit politician our mayor was. The rain lent Lee’s an insular magic, secure and dry and amongst friends.

Nelson Manders was an old man living his retirement in eternal resentment because he was old. He scowled at everything, a squint eyed frown and flinty star that cowed most people into avoiding him. Deep into his cups, he complained incessantly about everything, especially his card partners.

“Fucking weather,” he grumped.

“Romantic,” I advised.

“You don’t have my bones, Davis,” Nelson snapped. Half of his conversation began with the phrase you don’t have my. To Nelson, God was a Lord of Inequity, and he seemed to always be on the wrong side of it all. Alone, I sometimes felt sorry for the miserable little shit. Sitting across from him, drunk and losing, I had no sympathy at all for the miserable little shit. I grinned sour-assed and toasted him.

“I didn’t think reptiles had bones, Nelson.”

His wrinkled face twisted up in an ugly way but his shiny little eyes shifted to Bobby, who was chuckling expansively. We all looked at him. Bobby Hiller personally voted five times in the mayoral election just past, and no one much minded. He was really the only one who wanted the job, anyway, and surviving a reckless, brawling youth had left him sly and likable. One thing was always true about Bobby: there was always more going on with him than met the eye. Any man who pretended to be drunker than he was in order to cheat as wholeheartedly as he did at a friendly nickel and dime game was not to be trusted. At all.

He shook his head in amusement. “Arguing ain’t gonna help your game, boys.”

He always called us boys. It annoyed Nelson to no end.

I raised an eyebrow, kicking my call in. “Call, you lucky shit.”

I didn’t glance at my cards. The rain outside was thunderous and encompassing, whispering. I knocked ash off my cigarette and looked at Terry, who was almost too drunk to play. He was peering blearily at his cards and mouthing something. I reached over and smacked him playfully on the head.

“Hey! Lushboy! We don’t have all night!” I snapped. We did, but didn’t like to admit it.

Nelson looked nasty. “Hmmph, our fine and famous writer, and the gilded phrases he offers us.”

I let my face tighten, but that was all. I covered it all with wit.

“I don’t waste the gilded ones on ilk such as you, Nelly. I give you the shit-talk.”

He bristled. He hated being called Nelly.

Terry folded, more so he could free his hands for drinking than any tactical reason. The game went on for a few more hands, Rilly pumped some slugs into the juke box and put some old Sinatra tunes in the air, which just made us all drink more. My eyes kept drifting to my picture of Mr. Lee. He seemed disapproving and mean-spirited that night. The empty seats around us were all kicked back from the tables as if angry customers had leaped up and left the building, possibly in the tapped-keg riots of Lee’s past. The rain had thinned out to a downpour, and for a moment there was the static relative silence of rain outside and nothing else. We were in-between songs on the juke, studying cards (or, in the case of Rilly, studying us) and not noticing the quiet. At least not until the bell over the front door tinkled.

There were a hundred people who could have come through that door and not surprised us. None of them did. The elderly gentleman with the big, heavy black suitcase looked like a drinker, his big nose was ugly and red, shined from many an obvious cup. His face was reddened and his eyes were watery, sliding from Rilly to us to Rilly. He was soaked to the skin, shivering and chattering. Still, he dragged a somehow familiar smile to his blued lips as he walked up to the bar.

“Good evening! Whiskey, straight, double, no ice please,” he half boomed, half panted. He was very out of breath, and suddenly didn’t seem at all healthy. His old skin was slack and loose, his breath ragged and rattling, his eyes thin and watery. I was the only one who stared at him for long; everyone else ignored him and concentrated on getting drunk.

Rilly served him his drink with the usual sneer, and the oldster sighed and leaned against the bar, facing us. I glanced at him and he raised his glass. I nodded.

“Hello, grandpa.”

“Rough night.”

“Romantic,” I advised.

He slugged back whiskey impressively. “For young men, maybe,” he gasped. “Not for me.”

I was in high spirits. “No one young here, grandpa.”

I stood up. Nelson squawked, but I just grabbed my drink and walked over. It was about time I had someone new to talk to. I held out my hand. His was cold and wet, clammy. “Tom Davis,” I said.

“Ronald Gladly,” he gasped. He squinted at me. “Tom Davis, do I – ”

Nelson looked up, grinning. “Yeah, ya might? Tommy’s our resident alcoholic author.”

I glared at him, but then got philosophy and smiled. “In a town of alcoholics, Nelly, someone’ s got to be the writer.”

Gladly laughed. “I think I did read one of your books, Mr. Davis.”

I sucked whiskey and grinned wetly. “Book, Mr. Gladly, book. Badly written and a long time ago. It still amazes me how many people I run into who’ve read it.”

“Us too,” Nelson quipped.

“Shut up,” I snapped.

“You gonna play?” Hiller asked.

I sighed, finishing my drink with a sick swallow and ordering another because I liked myself less and less every day. “I fold, Bobby.”

He nodded, satisfied.

“What do you do, Mr. Gladly?”

His smile was fleeting and meaningless, and it struck me as odd in the fact that it seemed the opposite of a smile – it was a gash. He fingered his drink and his eyes slid to glance at his black case.

“Me?” He seemed suddenly nervous. “Bibles. I sell bibles – Hello ma’am, I was wondering if I could steal a few moments of your time – bibles.” He looked at me and suddenly seemed self-conscious. “It’s hard to sell bibles in a godless country, Mr. Davis.”

I laughed drunkenly. “It’s hard to sell books in a stupid country, Mr. Gladly,” I said, unadvisedly, I guess.

He nodded, looking careworn. “I see, Mr. Davis. The world is so clear when you have a writer’s mind to see it with.”

It smacked of flabby, tired sarcasm, but I ignored it, deserving of it as I was. I lapped up abuse. It was the alcoholic’s real drug. It gave us a reason to be losers.

”Not claiming anything of the sort,” I protested expansively. “Just chattering. That’s what we do best here at Lee’s. Much talk about nothing. Cards?”

I gestured at the table and ignored Nelson’s scowl. Nelson didn’t like people, but if he had to choose, he chose people he knew.

“Well – ”

I didn’t let him think too hard about it. I pulled him along with me and pulled out a seat next to Terry and myself. “Let’s be friendly.”

Bobby smiled and nodded. “Good to meet ya, Gladly. Sure a man of faith should be gambling?”

Gladly seemed to find the comment amusing. His slack face drew itself up into a horrible grin. “I sell bibles, sir. I don’t read them.” He laughed. I paused to stare, but Hiller nodded and laughed along, pleased.

“Hah! Just so, then, Mr. Gladly! Bobby Hiller, mayor during the day.”

Gladly nodded back. I shuffled and dealt and he held his cards like a pro, squinting. Nelson scowled, Terry dozed, Bobby won, and quite suddenly it seemed like the night wasn’t going to be so different, after all. The town, this place, the people – we absorbed, and resisted change. We made the new our own or we drove it out, feast or famine, love or hate.

It was the first time I realized that our time was coming.

####

Gladly played badly, drank with practiced ease, and took a room from Rilly as the sun began to pink the sky. I sat with Bobby in the dawn, smoking cigarettes, listening to Terry snore. Nelson had gone home when the place had officially closed, hours before. “You don’t like him.”

I looked at Bobby. In the light, he was looking older. “Who?” I asked cagily.

“The bible-seller. At first I thought you did, but not now.”

I sighed. I had been awake too long, and my mind was playing tricks on me. I rubbed my eyes and realized I had an unlit cigarette between my fingers. “Bobby, he’s gonna ruin us.”

“What?”

“The pictures, Bobby. The pictures.”

“What? You okay, Tommy?”

I looked over at him, slowly. I smiled. “Yeah, Bob, yeah. But how much you wanna bet that our new friend Mr. Gladly’s been here before?”

Hiller smiled, relaxing. “Get some sleep, Davis. You’re not feeling well. You can’t hold your booze like a young man any more.”

“I am a young man,” I muttered. I stood up, creakily, and looked around, the sea of black and white, the crowds of long gone and forgotten people, the static universe, whirled by. “See ya tonight, Bobby.”

“Yeah.”

####

I showed up showered and more or less sober, doomed and not at all inclined to do anything about it. I asked Rilly if Gladly was around and he said he was. I ordered a gin and soda for a change and smiled around the room. I knew most everyone in the place, but no one I wanted to see was around, so I took my glass and wandered to the far wall, covered in the faded photographs.

The great Tapped Keg Riots photo was hung eye-level and I sipped bitter liquor as I studied it yet again. Never noticed in its background, in the mirror hanging on the far wall, the slim half-image of the photographer leered. He was crouched forward, elbows out, his aged and obsolete camera on a tripod, his face hidden by the sudden, hideous flash.

I stared at it until I noticed Nelson next to me.

“You getting punch-drunk, Davis?”

I smiled at him. “Better weather.”

“Too damp.”

“Not,” I countered giddily, “compared to yesterday.”

He didn’t have much to say to that, so he just made faces at me. We sat down at our table and argued until Mr. Gladly appeared. He looked much as he had, just dried out and rested, as he took a seat at our table, shaking hands heartily.

“Well, gents, I’ll be leaving you on the morn,’ he announced. “Time stops for no man.”

“And here you haven’t tried to sell us any bibles.”

He looked at me strangely. “Mr. Davis, I don’t peddle to individuals. I sell in bulk to hotel and motel chains.” He smiled. “If you wanted a bible, I’m sure you could find one.”

Nelson was getting bored drinking the same stuff he always got drunk on. “Shall we play?”

I glared. “We’ve got to wait for Terry, for Bobby.”

“Yes,” Gladly put in. “You’ve all been very kind. I’d like to see you all before I leave.” He sighed. “It’s usually so lonely in places like this. You have made it otherwise.”

Nelson would not be consoled by flattery. He gripped his glass grimly and hunched over it. “Why, so we can watch Terry pass out and go broke to Bobby?”

“Sure.” I grinned. “What else do we do? Tradition’s better than nothing.” The end didn’t seem so bad. It was familiar. And with it, I supposed, a bit of minor immortality.

Gladly chuckled at that, and Nelson, of course, scowled. It was etched into his face, fine lines of disappointment and disapproval.

“Oh!” Gladly half-shouted. “I have a good idea. I’ll be right back.”

He stood and headed for his room. I felt an odd peace settle on me, and as I met Nelson’s frown, I had no urge to hit it, which I took as a good sign.

“You look like a goddamn Cheshire Cat,” he snapped.

I shook my head. “No smile.”

“Just as smug. What tickled your ass?”

“I was just right about something.”

“What?”

I glanced up from his bitter eyes. “Hello, fellows.”

“Hey, Tommy,” Bobby nodded at me as he hooked a seat his way and sat down. Terry looked like he felt good for the first time all day.

“How’s tricks?”

“Slow, today.”

”Where’s our bible thumper?”

I squinted behind him. “Three o’clock.”

Hiller turned and waved. “Mr. Gladly! Still with us, eh?”

“One more game before I leave, yes,” he huffed, sitting down. He had a black leather case cradled in his lap. “Even if I do leave on a losing streak.”

“What’s that?” Terry murmured.

As he lifted it out of its case, I couldn’t help but smile.

“A camera,” I said.

He grinned. “Yes. Black and white, I’m afraid, but good enough for mementos.” He stood up. “May I?”

We were all suddenly nervous. “What should we do?”

“Just act like you’re playing cards. Try to be natural.”

“We picked up random cards and smoked to appear casual. Gladly moved off and focused, and just as I got antsy and turned to say stop it, don’t take our fucking picture, he clicked the shutter and I got flashed in my eyes.

When it all cleared, Gladly was sitting next to me and the photo was on the table.

####

It was a stark photo, much too big for the camera – and anyway developed far too quickly. It hadn’t been an instant camera. But the photo was there, hard light separating the four of us, cards held loosely, cigarettes chewed on, drinks held tightly. I glared back at the camera with a cigarette between my lips and smoke obscuring my face. I couldn’t believe I looked that old. We all did. Bobby had a smirk on his face – thinking that it was all silly, most probably. But in the picture it made him look like he was bluffing and couldn’t hide it.

Nelson wasn’t scowling, for once. He had a shifty, squint-eyed expression on his face, looking sideways at Bobby like he didn’t trust him. He was holding his cards like he didn’t need to look at them, like the outcome of the game wouldn’t matter.

Terry was hidden behind me, just a shape. You couldn’t tell who he was. Or what he was.

####

We played. The night went on unopposed and the photo sat in front of me. I stared at myself. After the sun rose, we kept playing, and not even Rilly complained. The day went on, and I passed out.

####

I woke up alone in an empty bar. The tables had been cleared, but someone had taken pity on me and let me sleep. Gratitude swept through me, and then left me scraped clean. I stood up and looked around, and felt it all drain away, the colors, the need, the desperation.

There on the wall, underneath Helen and far from the great tapped keg riots, we sat, playing and staring, forever, eternal. I could only stare back for a moment, and then I turned to go.

Yes, at least you were paid!! This year I submitted to 15 mags and ended up rejected “and” broke. Maybe next time then.

The best part is when you *sell* stories and still wind up broke!

Your style of developing character is already evident here. Very enjoyable for me as a fan.

“Glad and Big.” Is the Glad a reference to Mr. Gladly? If it is, what’s the Big?

No answers required, just thinking aloud.