I’m a writer who’s obsessed with his own statistics as proof of his existence. This dates back to long before I started writing, in fact; I have every book I’ve ever read, for example—every single book—because the sight of all of those physical spines on a bookshelf is evidence that I am here. I have every baseball card I ever bought for the same reason, and also because of the mystical relationship between baseball stats and my own personal existential scorecard. Barry Bonds may have hit 73 home runs in 2001, but I read 37 books that year, and wrote 12 short stories and 2 novels1.

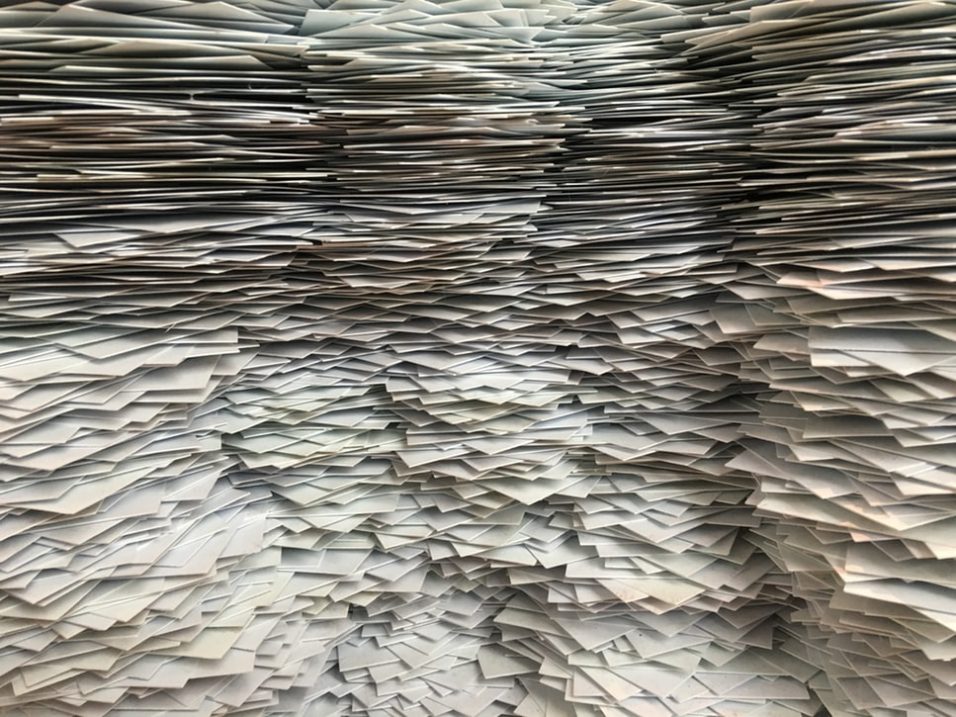

Over drinks recently a fellow writer told me they still print out hardcopy of their work each and every night2. Whatever they’d managed to write that day, they printed. They had stacks and stacks of paper everywhere, monuments to their work. I experienced a pang of regret, because my desire for those same kinds of monuments has run straight into my desire to live in the future, because like a lot of people, I’m running a 100% paperless writing career right now3.

But I miss the paper.

Stacks and Stacks

I held out for a long time. Until some time in 2005, I wrote all my fiction on a 1950s manual typewriter I stole from my sainted mother. Every story, novel, and failed experiment was tapped out on that old machine, resulting in a new stack of tidy white paper to add to the existing stacks crowding my apartments4. Moving house was a logistical nightmare thanks to the books and the manuscripts, and I quickly ran out of friends willing to show up for a slice of pizza and a beer5. That was okay, because all that physical paper reminded me that I was there. I had done things. Those ideas and stories weren’t just my imagination, I’d made them real.

It’s different today. Are the new ideas real? I don’t know. I have an obsessive spreadsheet where I keep track of finished works, and the numbers are comforting6. But it’s not the same. First of all, unfinished works have their own charms to the writer7, and they are invisible to the spreadsheet. And all those ones and zeros—no matter how many clouds you back them up to—exist only because civilization exists, because of the power grid and the technological infrastructure. When the world ends, and it inevitably will, when everything shuts off, in a split second everything I’ve ever created will more or less vanish until some super-evolved species of ant rises up from the radioactive slush and re-invents computer forensics.

In so many ways, the modern writing career is an improvement. Research is a matter of a few clicks. Submissions don’t require a trip to the post office8. Social media allows me to pretend to be much, much more successful than I actually am. And, yes, I can now move my entire life’s work to a new house by sticking a thumb drive into my pocket as I leave9.

But I miss them, the stacks of paper. Because if the health department isn’t called to my Collyer Brother-like mansion because I have died after being trapped for weeks beneath a collapsed pile of ancient manuscripts, did I even actually exist10??

- Barry made slightly more money.

- I am so thoroughly bourgeois my first thoughts went to the insane cost of printer ink.

- Often also a 100% moneyless writing career.

- I am old enough to have manuscript copies that were generated using carbon paper. That means I am somewhere between the age of the pyramids and the birth of the universe old.

- Which of course meant I ate all the pizza and drank all the beer and was thus rendered incapable of doing any physical labor and long story short I am still living in that apartment, and will be forever.

- Except for the cell where I calculate the percentage of submissions that have sold. That number is … not comforting.

- The main one being that if you never finish it, there might still be a way to salvage it. Refusing to stop writing the last chapter is like when contestants on The Voice hold their final note for 15 minutes hoping a judge will press their button. I just admitted I watch The Voice and I have regrets.

- I have known the inexorable sadness of self-addressed-stamped-envelopes with postage, soggy with tears, dolor of line and stamp glue.

- Chances I do so while dropping a match and setting the place on fire in a complex insurance scheme because writers get paid in sadness and insults? 100%.

- Trapped Under Something Heavy’ is honestly #14 on my Big List of Potential Deaths. It’s why I always carry Kind Bars in my pockets.

Data storage is easy for us. Too easy. My own internal data banks contain many times more information than all the material books ever created by anyone anywhere. High-capacity high-speed data banks are great, but they are a double-edged sword. You can access them rapidly – but they can be erased, corrupted, and counterfeited just as fast. One moment you have the sum total of all knowledge at your fingertips, and the next moment, nothing but random numbers, or worse, subtle lies. And even though we can store vast amounts of data, usefully searching and looking for connections between separate entries can take nearly forever even at the speeds we think at.

Double-Wide founded his Physical Library centuries ago as a control. It contains only printed physical books, with all the information encoded in patterns of light and dark on thin pages of various durable substances. Many are in human-language words, some contain pictures and diagrams, others are visual encodings of gestalt data structures. The library occupies a space of about one-tenth of a cubic kilometer, packed with physical books. The data contained in the library is tiny, not even a percent of what my own nearly-obsolete systems hold. But the information contained in the library is precious: enough to recreate our entire civilization from scratch, if need be.

The physical library cannot be hacked, or bulk-erased, or accidentally destroyed by a minor glitch in a software algorithm or an unlucky hit by some stray cosmic rays. The discipline needed to compress our knowledge to this level has resulted in a parallel electronic database that is small, easy to upload, and easy to search.

The physical library is also resistant to tampering in a way that no electronic library could ever be. Imagine that a piece of data is stored as the pattern of bits in a circuit:

00111001111

Those bits could have been set a thousand years ago. Or they could have been altered in the last second. Electrons have no hair; one looks just like another. But now imagine that this data is encoded as a pattern of ink on paper. It cannot be remotely altered. A physical agent would have to change the physical arrangement of the ink molecules. But the ink and the paper have complex patterns of trace elements and isotope ratios. The weave of the paper fibers, the structure of the cell walls of the trees used to make it, the remains of micro-organisms embedded in the book from the time of its construction; matching this perfectly in altered and original sections is difficult if not impossible.

So far as we know the universe does not care what we do, but it can be fun to anthropomorphize. The Universe acts as if it hates order, and whenever order arises it sends its invincible attack dog Entropy out to tear it down. As technology develops the ability to store petabyes and more in compact high-speed devices, the Universe seems to take it personally. It gets pissed off, and Entropy attacks in a thousand different ways. We make multiple copies of our data, we use the most sophisticated error-detection and correction algorithms, but that just seems to make the Universe even angrier, and bit-rot and data corruption continues to plague us.

The Universe doesn’t like data stored in simple physical artifacts like stone tablets or books either, but the amounts of data are so small that the Universe is lazy about wearing it down. Stone tablets will weather, paper books will rot or be eaten by rats, even etched hyperloy will eventually decay as one atom at a time moves out of place. But here the Universe is in no rush, and with the right materials something with the data capacity of an old human book can easily span megayears.

From “The Chronicles of Old Guy,” Ballacourage Books.