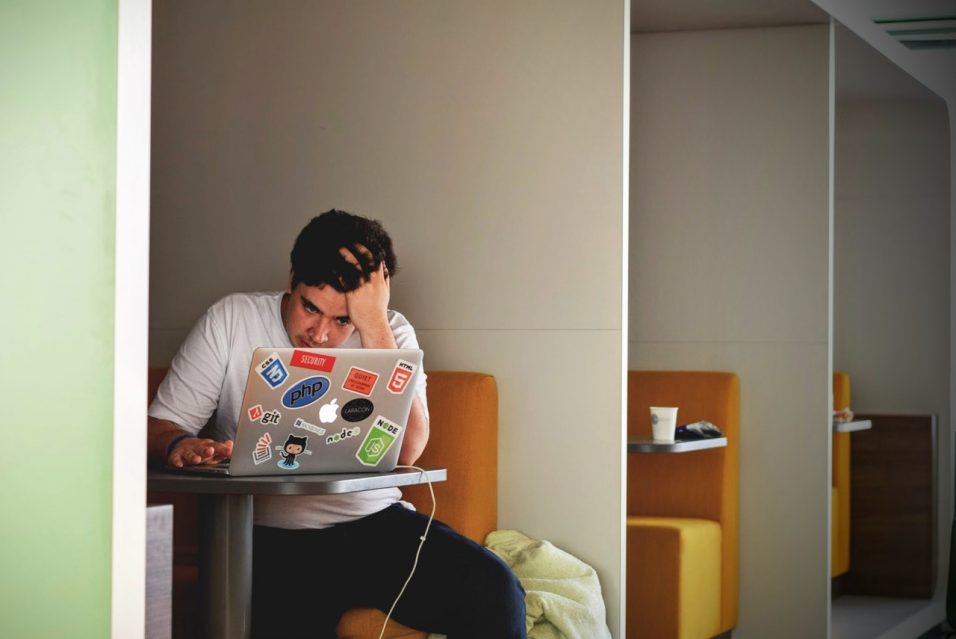

Writing novels ain’t easy. Heck, writing short stories ain’t easy. Well, in some senses it’s easy; sometimes having an idea is the easiest thing in the world, and even whole sections can fly off your fingers so fast and perfect it seems like you should be able to write, like, a dozen novels a month. Maybe more.

Ah, but then—as every writer knows—comes the doldrums, those slow times when not only can’t you seem to get the words right, you also can’t seem to even have an idea. Everything feels leaden and dead and the idea that you might ever write a complete story again seems depressingly ludicrous.

For those moments, I recommend drinking heavily. Actually, drinking heavily is my go-to medicine for just about any writing-related, but especially those horrible moments when it seems like your Muse has abandoned you.

There’s another horrifying moment for writers, one that gets a lot less attention than the big bad Writer’s Block. It’s the sudden downturn in energy and productivity that sometimes follows completing a major project—The Aftermath of a novel can be brutal. I should know, I didn’t just complete one novel, I completed two, as well as a short story. And I crashed hard.

The Come Down

I wrote several novels over the last 2 years—four of them, to be exact. Two weren’t quite great (and one of those I managed to pare down to a short story that contains the essentials, leading me to believe that I was way over-padding that premise). But two are very good, in my not-so objective opinion. I worked on them concurrently for the last few months, jumping back and forth between them. And when I finished them, very close to each other, I was very happy with the results.

Since then I’ve been … well, struggling’s not the right word. It’s been slow, though. I don’t have a big project in mind, and the smaller pieces I’m working on aren’t exactly pouring out of me.

I’ll get there, I always do. And that’s what’s necessary in these moments: Faith in yourself, in your own idea machine. You have to remind yourself that the tens of millions of words you’ve written over the course of your life (or the thousands, or the hundreds) all came after periods of struggle. It happens, it’s not a big deal, and it will pass.

Aside from, you guessed it, drinking heavily, my antidote to this crash is to work on as many short projects as possible. Short stories can get a lot of half-baked ideas out of your head—some of which might become fully-baked with a little time and effort—and keep your fingers moving until your lizard brain shrugs off the malaise and gets cranking again. When that happens, you want to be ready. Although the drinking never hurts either.