The Power of Skip

I’ve always been a champion procrastinator. It’s a shame cycle: I put off doing things, even things I ostensibly enjoy, until I suddenly wake up in the middle of the night with a vision of my own impending mortality, and then you’ll find me sweating freely at 3AM as I work doggedly at four or five projects simultaneously.

Is almost everything I do driven by fear of death? You betcha. Except whiskey. I drink that for the love.

Of course, a lot of these unfinished projects are novels and short stories and weird metafictional thingies that I started working on in 1989 and now exist as 60,000 separate files in various word processor file formats.

What’s crazy about this is that I love writing. It’s the one thing I will always choose to do, one of the few things I’m just as enthused about, if not more so, than when I was a kid. And yet the main thing I procrastinate about is writing.

Who Will Finish All These Novels?

One reason for this that most writers will understand is simple: Creating a story can be damned intimidating. You look back at what you wrote last year and the process is mysterious, the inspirations opaque, the tricky bits impenetrable. How many of you have ever re-read something you wrote a few years ago and discovered you don’t recognize it, it’s like it was written by a stranger. That’s happened to me, and it can make starting something new kind of scary. After all, you can’t repeat a trick you didn’t understand in the first place.

What makes it harder, often, is the sense of heavy lifting that some aspects of a story can inspire. There are always bits of a story you’re excited to write, and bits you’re not so excited to write but need to be in there anyway. Often a story will begin with a burst of enthusiasm and then you run into a less-exciting bit and your brain issues a stop work order.

In those moments, a good way to deal with it is to skip those parts.

Skip It

There’s a tendency to think you have to follow rules when you write–but your process is your process.

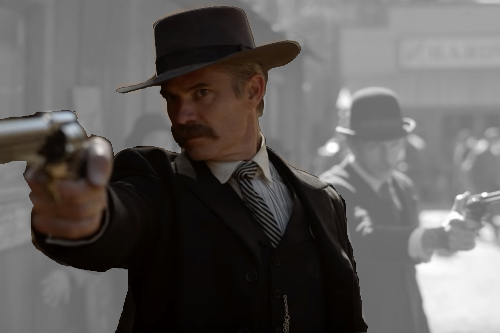

Ian Fleming, who wrote the James Bond novels, had a remarkable process: He would write the story, the entire plot, without bothering with much detail. The end result was a skeleton of a book, but it had all the plot twists, dialogue, and characters. Then he would go back and revise, adding in the sumptuous details of Bond’s globe-trotting life.

In other words, Fleming skipped stuff he either wasn’t interested in or found challenging at that stage of the project. Then he went back and did the same.

You can skip anything. Skip the boring parts, the exposition and necessary mundane sequences that are required but unexciting. Skip the explanations and just keep moving; you can go back and explain (or figure out) what it all means in revision. Skip the details like Ian Fleming. Skip the dialogue! Why not. Any time you pause and think you’d rather not write this next bit … don’t. Put in a marker, move on to something you do want to write, and enjoy yourself.

Of course, you can go too far with this. Decades ago I skipped wearing pants, and look where I am today.