Grandpa Terminator is Making Me Sad

In which I watched Terminator: Dark Fate so you don’t have to.

1984’s The Terminator is a delightfully deranged, violent sci-fi story that somehow combines Linda Hamilton’s 1980s feathered hair and Arnold Schwarzenegger’s inexplicable Austrian accent and improbable body into a near-perfect story. Sure, it’s trash, but it’s very good trash, at least for some of us.

A sequel should have been a disaster. It shouldn’t have worked. But somehow James Cameron avoided simply remaking his first film with a bigger budget and managed to surprise viewers with a story that cleverly flipped the hero/villain dynamic. Making Arnold’s Cyberdyne Systems Model 101 Series 800 Terminator the good guy, then having it stumblingly learn why human life is important, was a (slightly stupid) very cool plot twist, especially when coupled with Robert Patrick’s slender-but-relentless Series 1000.

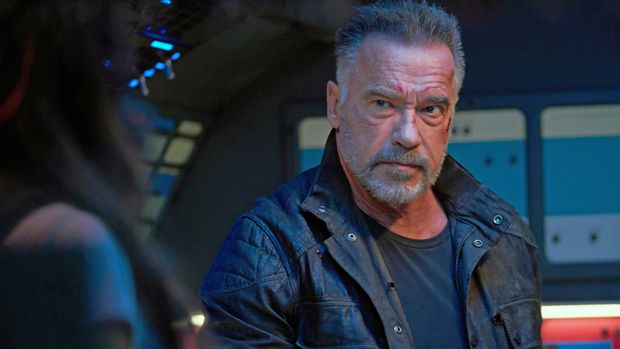

Alas, like Daffy Duck’s gasoline and dynamite schtick, it’s a trick that only works once. Watching the horrifyingly terrible Terminator: Dark Fate the other day, I was struck by the fact that the diminishing returns on the T-800 Terminator learning how to be human have slipped down into negative numbers. This is an idea that has to stop.

Villain Decay

Since the glorious days of 1992, there have been four major films in the Terminator franchise: Rise of the Machines, Salvation, Genisys, and 2019’s Dark Fate. Rise was a second sequel, and was relatively successful despite being a pretty boring retread of the previous films’ tropes. But at least it still had a relatively young Arnold Schwarzenegger (he was 55 during filming) who could at least look like a deathless killing machine.

After that, the franchise fell into a pattern: For three films, they’ve been trying to reboot the series, failing miserably, and then trying again.

2005’s Salvation tried something different. Set in the post-apocalyptic future, it tried to leave Schwarzenegger behind; Arnold only appears as a brief, CGI version of his 1984 self, the original T-800 model in a tiny cameo. If only Salvation had been a brilliant film and a huge hit, because the last two movies have been stuck with Grandpa Terminator, and it is terrible.

Everyone likes Arnold Schwarzenegger, and there’s no sin in growing old. But after the failure of Salvation, the film studios took a look around and obviously concluded the film failed because of a distinct lack of Arnold-style Terminators. And the only solution they can think of is to keep bringing Arnold back as an increasingly ludicrous killer robot.

WHY DO YOU CRY

The explanation for why a soulless killing machine would age and grow old is just barely acceptable, and then only if you’ve already suspended your disbelief to the sky-high levels these movies require: The T-800 is covered in real human flesh, complete with blood vessels, in order to fool the future scanners of the resistance. That flesh ages, even as the robotic chassis beneath it remains immortal or as close to it as technology can make it.

Sure, that makes no sense, and doesn’t explain why Old Man Terminator walks like a stiff, 73-year old man in pretty good shape, but fuck it: It’s Terminator Town. I’ll allow it.

The real problem is in Dark Fate‘s extension of the learning-to-be-human trope established in Judgment Day, where John Connor gives the T-800 simple lessons in how to be human, culminating in a line of dialogue that still makes me want to kill someone every time I hear it:

Yeah: That’s terrible.

The whole “robot learns value of human emotions” isn’t exactly a new trope, and the decision to double down on it with Grandpa Terminator in Dark Fate is a terrible storytelling decision in a film filled with them. The T-800 in Dark Fate isn’t the same one from either of the two original films. There were several Terminators sent back in time, and after the end of Judgment Day one of those other ones found John Connor and, er, terminated him. Then it walked away, its mission accomplished, and instead of self-destructing or something else a real, programmed machine would have done, it goes off, starts a drapery business, and hooks up with a single mother.

This is real. This happened.

So we have Grandpa Terminator pretending to be the asexual stepfather of dreams, because apparently all Terminators have secret subroutines or unlockable achievements concerned with being a father figure. Which is a remarkable thing for an evil AI to introduce into the design, if you ask me. This leads to Grandpa Terminator doing all sorts of goofy old man schtick, like a lengthy monologue about talking a customer out of some really bad drapery decisions, and the sight of Grandpa Terminator sitting in a lawn chair that miraculously supports his 400 pound weight, passing out beers to everyone.

There’s a broad strokes argument for this sort of nutty twist, but it falls apart in practice. This is just terrible character work, necessitated solely by the desire to have Arnold Schwarzenegger in the film as the T-800 without just going ahead and animating him.

So: Mistakes were made. Someone made this movie, for example. And I watched it, as another example. Take some lessons from my shame: Playing around with making your villains into anti-heroes is fun, but it comes at a price, and that price is usually the ruination of the character. It’s a trick that works once, and you should be aware of it before you go Grandpa Terminator in your own story.