Glad and Big

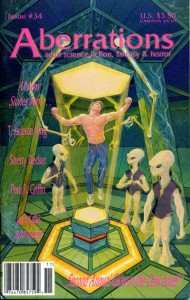

“Glad & Big” was the first story I ever sold for real, actual money. Written in 1993, it was published by Aberrations Magazine in issue #34 in 1995. I was paid 1/4 cent a word, or $7.50. I never cashed the check and still have it. In 2014 dollars that’s $12.19. By the time I die I hope it hits at least $20 so I can start saying “I got paid $20 in today’s dollars!”

This is very clearly, to me, an early story, right down to the narrating protagonist who happens to be a bitter writer, because all lazy writers make their characters writers as well, because we don’t know anything about anything else.

——————————–

Glad and Big

Life at Lee’s on second street had a pattern, one I liked well enough. It sucked at my heels with insistent attraction, pulling me back despite the heat and the same old people and the wooden seat worn smooth from years of my weight.

We usually played cards at the small square table in the big bay window, eating Lee’s filling specialties and drinking, smoking cigarettes, and ignoring everyone else. Sometimes I tried to stay away. It never worked. I always needed a drink and the only place to get one was Lee’s and my seat was always open.

That night it was raining and I felt pretty good. The conversation wasn’t too bad and it was warm inside, I was half-tanked all night and I had three packs of cigarettes to get through. Even in a crummy bar and grill like Lee’s, being inside with friends on a rainy night is a special kind of thing. Even being inside with people who drove you crazy like I was was still not bad.

###

It was an old, run-down place owned by a hundred different people so far, with a truckload of future owners down the line waiting to be suckered. You walked in, the old hardwood floor creaking beneath your feet, and the bar stretched off to your left, far too long, too far into the shadows, built in more optimistic times when booze was cheaper. Tables and the rickety wooden seats they required filled the rest of the floor, never crowded but always occupied.

The walls were three generations of photographs, mostly black and white. They stretched back into the past too far to be remembered; now they were meaningless portraits of people we’d never met, moments in time we couldn’t interpret. They wrapped around the back wall and behind the bar, big and small, some dated and some not. We each had our favorites.

Nelson, the crotchety old bastard, had a soft spot for Helen. She was a brooding, sad-eyed young girl in a bullet bra and a tight, tight turtleneck, sipping coffee, framed by the bay window. She had a Sixties hair-do and in the corner she had written “to Tony – always – Helen.” The steam rising from her coffee, the way she glanced away from the camera. It entranced the old fuck.

Terry liked the one with the big crowd. It was one of the oldest ones, and it showed old Lee’s filled with smiling, jostling, shoving people. There was pandemonium in that picture, static chaos. We all theorized that it had been taken just before a riot, just before the taps ran dry and drove the proles crazy. Terry didn’t have too much chaos in his life, but he desired it. The picture made him feel like it was all at his fingertips.

Me, I like the picture that had to have been the first one there, right behind the bar, framed. It was a dour, lean man wearing a bowler cap and a white apron, leaning behind the bar and staring at the camera fiercely. A small plaque on the frame declared him “Mr. Lee.” The first owner, I guessed. His name survived but not his memory – if asked I liked to say I thought he’d died in the great tapped keg riots of Terry’s picture. We were the only ones who got it, but then we were the only ones who mattered.