Resist Your Rut

The other day I went to the grocery store with a short list of items on a list, one of which was a certain kind of popcorn my wife, The Duchess, likes. In the popcorn aisle, however, there was confusion and despair, because I couldn’t tell which one of the several dozen varieties of popcorn my wife intended, so I took a photo of the choices and sent it to The Duchess, then called her as I moved on to gather the other items on my list. We chatted about all things popcorn while I shopped, she clarified her request, we hung up, and then I checked out without actually going back to buy the popcorn. I simply forgot all about it.

Routine is my friend largely because my memory has always been epically poor; I forget things within moments. If this were a new development in my dotage I’d be worried, but the fact is I’ve always been this way. I can forget things at a worrying pace. There’s a weird moment I’m aware of when thinking about something somehow clicks over to having done it in my brain. Like the popcorn: I thought about buying it, and therefore my brain reported it as having been bought.

As a result, I like a good rut. Putting things in exactly the same place and doing things in exactly the same way day in and day out helps me to remember things like my wallet, keys, and phone, and a routine helps me to always go to the places I need to be. Yes, I’m like a brain-damaged puppy, what of it?

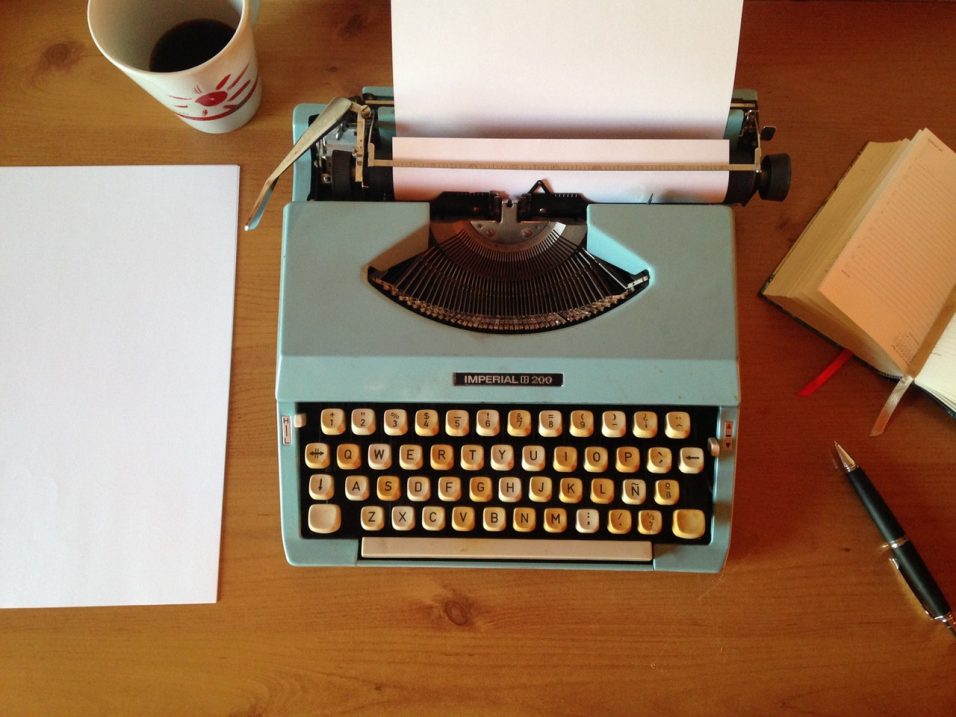

This extends to my writing; I like a good rut because it means I will always find time to write. If I wing my schedule, writing often disappears because I simply run out of time. And I like to approach writing ritualistically because doing it the same way every day helps ensure I actually, you know, write. Without a routine and a rut, I’d be lost.

But sometimes, you have to break out of your rut.

Seeing the Rut

Ruts and routines are useful for getting work done, but not always useful for inspiration and creativity. Finding the balance between a routine that allows you have time to write and get words on the page and a sense of adventure that allows you to, you know, be creative and produce good work is always going to be a challenge.

One thing I try to do is to simply swap some time. For example, normally I work on freelance pay-the-bills writing in the morning and get to fiction in the afternoon, because I like to feel like I’ve paid some bills before I have fun. But sometimes it’s useful to push the freelance work and put some time into a novel in the morning. It feels like a fresh field of snow to write at a different time of day, and it tricks your brain into seeing things fresh.

Of course, even a new routine will slowly lose its freshness and become a new rut. You have to surprise yourself on a constant basis. And when in doubt, just start day-drinking. Any writing you do while drunk will be crap, but believe me, nothing blows up your routines like having a killer hangover at 3PM.