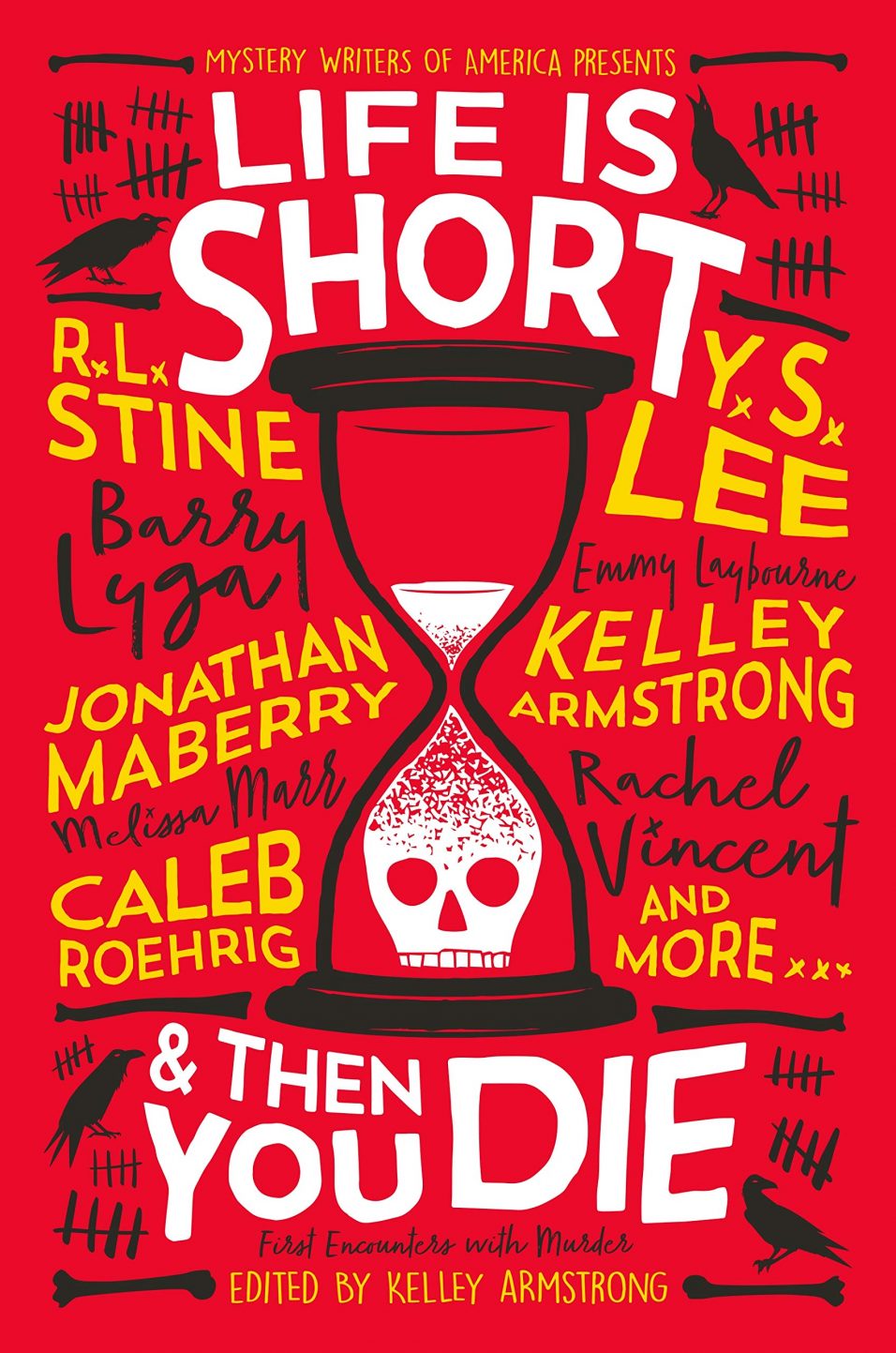

This month I have two short stories publishing; “The Company I Keep” appears in the YA Mystery anthology Life is Short and Then You Die, edited by Kelley Armstrong, and “Zilla, 2015” is up over at The Lascaux Review.

I’m extremely proud of both stories, and pretty excited to have them out in the world. As anyone who has seen me talk about writing in public knows, I want to basically publish everything I’ve ever written, good or bad. So having two stories out in one month is kind of exciting.

What’s interesting about these two stories, at least to me, is that they both started off as novels. And after writing ~100,000 words between them, I wound up with about 10,000 words worth keeping.

The Company I Keep

The Company I Keep officially began life in November, 2014 as a book about a man investigating the death of his college roommate 20 years after the fact. I began folding in material from a book about a mother who poisoned her children as a form of punishment, and spent a solid four years, off and on, trying to make the story work. In 2015, I had a 30,000-word novella that I liked but didn’t love; it had a nice sharpness to it, but felt meandering. So I put THE END on it and made a halfhearted attempt to submit, but then began working on it again.

In 2017 I had a 61,000-word novel that I knew better than to try an publish. It wasn’t terrible, but it also wasn’t good. I’d added a lot of backstory and business to it, but none of it felt consequential. Along the way, I’d played with the age of the characters, and the main character had evolved into a sort-of genius, a kid smart enough to attend college when he was 16 but not smart enough to actually do anything with his brains.

But I liked the Voice. I liked the main character. And I liked the mystery. When I read about the MWA Anthology Life is Short and Then You Die, which was looking for YA mystery stories focused on seeing your first dead body, I thought, The Company I Keep would work if it was 6,000 words long instead of 60,000.

Unless …

Yup. I cut that novel down. I deleted 90% of the words. And I sold that story to the anthology. Which either means that I’m a terrible writer who has to throw away 90% of his work before he has something decent, or that I need a bit of help identifying when my idea doesn’t really need 60,000 words to get through.

Zilla, 2015

I’ve had a poster of Edward Gorey’s Gashlycrumb Tinies on my wall for years now, and had an idea about writing a novel where the Tinies didn’t die as kids, but were being murdered one by one as adults. In May, 2018 I started working on that novel, and never got very far, though I did work up a great deal of detailed background information regarding the characters (all 26 of them, natch).

In early 2019 I decided to make one last try, and began work on a bit that would act as a prologue for the novel, detailing the last days of Zilla. I liked what I did, a lot, and was optimistic about working up a novel around the concept.

Yeah, that didn’t happen. I flailed around for a bit, trying different ways back into the story. Then I began working on another novel which occupied increasing amounts of my brain, and eventually realized that the Zilla story was actually the point. That short story was what I’d been working towards for more than a year, I just hadn’t realized it. So I cut my losses and sent Zilla, 2015 to The Lascaux Review because it seemed like a good fit. And sold it.

What’s the lesson here? There doesn’t have to be one, but I suppose one take-away is that you can get hung up on an idea being this or that, when what you should be doing is seeing where those ideas take you. Or maybe the take-away is that even in failed novels you can often salvage something good.

I’m proud of these stories. I hope you read them and let me know what you think. And if you’re struggling with a novel right now, maybe you can pull something out of it right now instead of spending another few months trying to squeeze literary greatness from a rock.

Or maybe I’ll go back and try again on both of these novels someday. Why not? There are no rules. Or maybe the rule is, Jeff need to throw away 90% of what he writes all the time. Which would explain a lot, actually.

I done did it again: A new episode of The No Pants Cocktail Hour is up for your listening enjoyment.

I done did it again: A new episode of The No Pants Cocktail Hour is up for your listening enjoyment.

Hey all—I was invited to join

Hey all—I was invited to join