Obscure Books

Because I am a cheap bastard, I frequent Used Book Stores a lot. There used to be a store in Manhattan where you could buy old paperbacks for $1 each; man, I did some damage in there. One of the benefits of frequenting Used Book Stores is the low barrier between you and books you’ve never heard of. In a regular store if I come across a book that looks vaguely interesting but about which I know nothing, the roughly $500 price tag might scare me back to the old familiar haunts of Elmore Leonard and Richard Morgan novels, but in a Used Book Store, what the hell. It’s only a few dollars. As a result, I’ve bought and read some strange and obscure books. The odd thing about them is for the most part they weren’t always obscure.

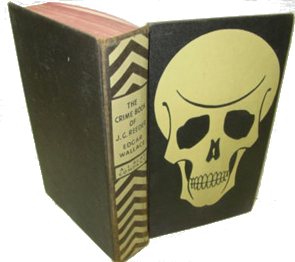

Which may seem obvious, but it’s weird to think of yourself as an aware and well-read person and then discover there are literally thousands of books that once sold very well, that were very famous, and of which you have never heard. Consider The Crime Book of J.G. Reeder. I bought this one day while wandering a street fair with The Duchess. The only reason I bought it, for $3, was the cover:

It just looked interesting. I’d never heard of J.G. Reeder or the author, Edgar Wallace (though I should have). Turns out, they were both quite famous and popular, and stories featuring the character of Reeder have been filmed a few times. Not exactly the Collected Works of Shakespeare here, but still, books that were at one time pretty big, and which now might as well have never existed.

They’re not even all that great, honestly. Some better than others, but one of the stories stands out as inexplicably bad: In Red Aces, the mystery Mr. Reeder is investigating is explained in a 2-page infodump at the very end, with absolutely no effort made to, you know, actually make it into an entertaining mystery story. You get the set up, the characters, some of the investigating, and then at the end a character you never noticed before is arrested and we’re treated to a memo filed by Mr. Reeder explaining everything, including tons of details that weren’t given to you in the story.

Okay. . .so maybe it’s not so weird that these stories are now more or less forgotten.

This isn’t new for me; I began my career of loving obscure book back in high school, when I discovered a series of Italian book by Giovanni Guareschi about a small-town priest in Italy named Don Camillo. My father had a paperback copy of a book called Don Camillo Takes the Devil by the Tail, which I read and really enjoyed against all odds. I mean, this is a book originally written in Italian in the 1950s – what are the odds? When I found four more collections of Don Camillo stories in my school library, I noticed they hadn’t been borrowed in 25 frickin’ years, so I offered to buy them. The school charged me $5 a piece for the four books, which I still have, and still enjoy.

The Don Camillo stories are just hokey fun, for me – they’re charming. There are probably about five other non-Italians below the age of 75 who have heard of this character, though.

It’s fascinating, this glimpse into the past. These books sold well, were made into movies, were comon pop-culture currency at one time. Today they might as well have never existed, except for the occasional lunatic like me who hoards them, gloating over books no one else wants. Even before I had my own set of books to watch anxiously sink into obscurity, I found books like these fascinating, not only because they were once popular and now forgotten, but for the insights into the psyche of a long-gone reading public.

You can see now why I was never one of the Cool Kids. But screw it. The cool kids read boring books.