Money

Visual Representation of My Writing Work

When I was a kid, I thought of money in fantastical and curiously practical ways. I never thought in terms of dollars and cents, but rather as packs of baseball cards and Huffy dirtbikes. When I paused to contemplate something’s worth, I would stack up packs of gum in my head, or paperback books.

My brother and I were given an allowance, tied to the dutiful execution of chores, but it wasn’t much. Anything more than the aforementioned baseball cards or the occasional candy bar would leave me penniless, so any sort of big purchase had to wait for my birthday or Christmas, and required the ceaseless and exhausting lobbying of my parents. Money didn’t mean anything, really; the only thing that mattered was the stuff that money could be magically transformed into.

I remember lusting for things. There was no such thing as instant gratification. I wanted a first basemen’s baseball mitt, a good one. When my mother took us to Sears for school supplies, I would wander off and stare at the gloves, signed by the greats. I would smell the leather and lust after them. I wanted a dirtbike, a shining, black bike that I imagined myself sailing into the air on. When my mother took us to Sears (my childhood is 34% Sears, 23% Two Guys) for family pictures, I would wander off and stare at the racks of bikes, imagining myself racing about the neighborhood on them.

None of these things cost money. They cost time and effort. I simply had to wait, and wait, and beg, and beg, and eventually, usually much, much later than I wished, they would be acquired.

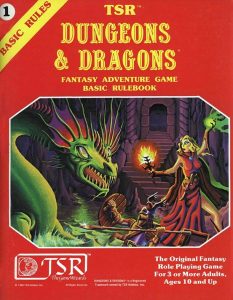

Today, as a working writer and a grown-assed man, not much has changed. I still don’t think of things in terms of money; instead of packs of baseball cards (thousands of which still languish in boxes in the house) I think in terms of freelance assignments or book advances. If I want a new phone, say, I don’t scheme to put a few hundred dollars together, I scheme to get three or four additional freelance assignments.

The digital age exacerbates this, because I don’t actually carry cash any more, an I get incensed when businesses don’t offer some way to pay aside from cash—not from any sort of idealogical position, but simply because I never have any in my pocket, so it’s a pain in the ass. Without actual dollars to pass out, the act of buying things and services is abstract, so I operate using a kind of unique, bespoke currency we can call Jeff Bucks. Jeff Bucks come in the form of freelance jobs and other miscellaneous sources of income.

Someday I dream of being able to pay for things by quickly composing a blog post on my phone while standing in line at the checkout. Or, more accurately, I don’t dream of that at all because my god that would be terrible, wouldn’t it? Imagine being the poor person behind me as I pull up the thesaurus to find synonyms of cutting-edge.