On Food Cannibalism in Commercials

Eat me.

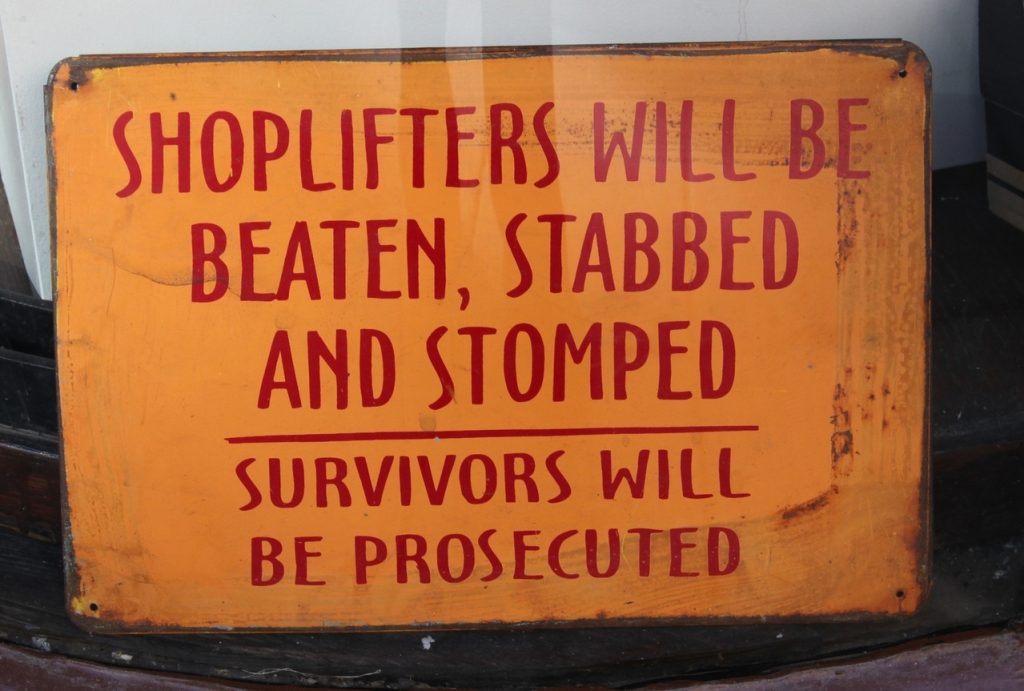

Let’s stipulate that two of the more disturbing things in this world are A) advertising in all forms and B) eating other living things for sustenance. Stipulated. Now, put those things together and generally speaking you’ll get some of the most insane, soul-killing stuff ever committed to paper or video, and anthropomorphic food is definitely at the top of the list. Every time a hot dog dances onto a movie screen singing about treats, I think about that fucking hot dog screaming in horror when someone eats him. The upcoming film Sausage Party gets this, since the entire film is all about anthropomorphic food that thinks being chosen at the grocery store is ascending to paradise, only to be completely horrified to discover what it really means.

So, as with most dark stuff, there’s humor there. Even so, sometimes there are commercials that are so ridiculously strange they make an impression—but what really makes you wonder if you’re living in a computer simulation created by aliens with an imperfect understanding of humanity in general is when the strange commercials all have the same weird, disturbing thing in common.

For example, food eating itself.

You’re Eating Yourself, You Don’t Believe It

Now, on the one hand anthropomorphic food eating itself—eagerly—isn’t necessarily evidence of anything beyond the fact that people working in advertising and marketing are the Worst People in the World (this is a fact, go look it up). I mean, if we imagine that Mrs. Potato Head actually exists as an intelligent, sentient being, then if she chooses to grind up her fellow potatoes and fry them up into delicious chips and then eat them, well, maybe sentient potatoes have different traditions and religious beliefs.

Dig the Trump Hair

Or if our breakfast cereal spends its free time chasing its fellows around so it can literally tear them apart with its teeth (teeth?) and eat them alive while they flee in fucking terror, then who am I to say otherwise? Again, maybe sentient cereals have developed a different standard of morality.

I see this in my nightmares, now.

These are just two of several advertisements for awful processed foods that apparently believe that cannibalism, terror, and the complete and total breakdown of society is an aces way to sell you horrible things. There are the M&Ms commercials, of course, which are not so much cannibalism as simply the predatory consumption of sentient, thinking beings who are completely aware that we all wish to consume them. I mean, seriously, this is a shitshow of psychological horror centered on convincing us to eat food we should never, ever actually eat. (Although, to be fair, Lay’s chips are fucking delicious).

My conclusion is inescapable: As I have long suspected, you all want to eat me.

I Am Delicious

Here’s my unbreakable logic:

- Advertising firms have the resources and motivation to get to the bottom of the human psyche. If they can crack the mind-control codes that stumped the CIA during the MK-Ultra years, they can make us give them our money for things like shit cereal that will 100% give you diabetes within a few years.

- Thus if all the trends in food advertising use cannibalism and the violent murder and consumption (usually raw) of sentient beings, the Advertising Illuminati must know this will appeal to you. Because you—yes, you—are a horrifying animal who secretly wants to murder and kill me.

I think I’ve proven my point: If you buy Cinnamon Toast Crunch, you’re a murdering cannibal. Or could be a murdering cannibal. Either way, I don’t want to be left alone with you. You can just mail me my Ph.D. in Thinking, I’ll just be sitting here drinking whiskey and watching far too many television commercials about predatory cannibalistic food.

In 2002, a year in which otherwise almost nothing I can remember happened, the New York Times reported that “a recent survey” confirmed the worst fears of many Americans:

In 2002, a year in which otherwise almost nothing I can remember happened, the New York Times reported that “a recent survey” confirmed the worst fears of many Americans:

Every now and then someone makes a terrible mistake and assumes that because I have published a few novels and stories and such that I know something about publishing and writing. I don’t. Like Jon Snow, I know nothing, and generally go through life feeling like a confused and slightly dimwitted teenager.

Every now and then someone makes a terrible mistake and assumes that because I have published a few novels and stories and such that I know something about publishing and writing. I don’t. Like Jon Snow, I know nothing, and generally go through life feeling like a confused and slightly dimwitted teenager.