In 2002, a year in which otherwise almost nothing I can remember happened, the New York Times reported that “a recent survey” confirmed the worst fears of many Americans: 81% of the country thought they could write and publish a book. Eighty-one percent. Considering there are about 319 million people in the U.S.A. alone, that means about 258 million people figure that someday when they have some spare time they’ll bang out a novel. Or, more accurately, they’ll go find a writer friend they know, drunkenly explain the story idea with helpful doodles on cocktail napkins as visual aids, and then let that writer friend write and publish the book while splitting the profits 70/30.

In 2002, a year in which otherwise almost nothing I can remember happened, the New York Times reported that “a recent survey” confirmed the worst fears of many Americans: 81% of the country thought they could write and publish a book. Eighty-one percent. Considering there are about 319 million people in the U.S.A. alone, that means about 258 million people figure that someday when they have some spare time they’ll bang out a novel. Or, more accurately, they’ll go find a writer friend they know, drunkenly explain the story idea with helpful doodles on cocktail napkins as visual aids, and then let that writer friend write and publish the book while splitting the profits 70/30.

At first blush, the 81% number seems high, especially when you consider that the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics counts just 129,100 authors and writers in the country as of 2012. Although, when combined with the explosion of self-publishing in recent years, that seems like a dubious number too, especially when you learn that the Bureau also claims the median income for authors and writers is $56,000 a year when most writers are constantly Googling “how to boil shoes for dinner” or “how long can I eat nothing but Ramen before getting scurvy”—although to be fair when you include people like James Patterson or Stephen King or E.L. James in the calculations, that median is going to shoot up quickly.

However, when you think about how many people participate in things like NaNoWriMo every year (more than 300,000 according to the website) and how many people are publishing novels—more than 750,000 traditionally and self-published books annually in the United States alone—it starts to seem like that 81% number might make sense after all.

In reality what this means is that an enormous number of people think they can write and sell a book, but less than 25% of them actually do, one way or another. That’s a big gap, even if we remove those helpful folks who are always offering up brilliant ideas for novels and seeking to split profits and restrict ourselves solely to people who would, you know, actually be willing to write a book. As an author myself, there’s only one explanation for the this discrepancy that makes sense: writing a novel is hella hard. Selling a novel is even harder. Black magic may be involved.

Authoring: Not as Easy as It Looks

If you’ve never tried to write a novel, it might seem like an easy, straightforward process:

Step 1: Come up with brilliant idea, interesting characters, detailed setting, and deviously twisty plot. Actually, this is technically Steps 1 through 3,500.

Step 3,501: Write at least 50,000 inspired words.

Step 3,502: Edit, revise, and proofread.

Step 3,503: ???

Step 3,504: Profit!

Anyone who has tried actually writing a novel can tell you that the process is a lot more difficult than this. Time is a huge factor: writing words that make sense takes a lot of time, and if you’re not able to write full time it can be tough to find those hours. Factor in things like children, employment and other duties, exhaustion, and hobbies, and the time to write your novel becomes increasingly elusive, and very likely won’t be your best hours of the day mentally, either. There are plenty of stories of authors who get up at 5AM like an Olympic hopeful, just so they can write for an hour before they have to go to their jobs. Patty Blount, author of Send and Some Boys, writes “… no more than an hour or two [a day]. Day jobs really put a kink in the fiction efforts. I am trying to adjust to a much longer commute and find I need to nap before I can write, or I can’t see my screen.” Sean Ferrell (The Man in the Empty Suit) writes “… on the New York City subway during my morning commute to work.”

And even if you carve out the time, inspiration can be a wily beast, always abandoning you (Tracy Kiely, author of Murder with a Twist, put it this way: “[Inspiration] depends largely on my Muse, who is unreliable at best. When she is in residence, I will write for four or five hours a day. When she takes off, I find myself reading Buzzfeed and shopping online for cute shoes. I have a lot of cute shoes.”) Characters or plot twists that seemed so golden to you when they first bubbled up fade away and curdle right under your typing fingers. Descriptions seem stale, style seems imitative, and that idea for a novel that had you leaping out of bed to jot it down into your dream journal dies an ignominious death at 15,000 words.

And—and this is the best part—no one is handing out medals just for finishing. You might work hard and create a novel, but that doesn’t mean anyone wants to read it. Or the second one you write. Or the third. I wrote six novels before selling the seventh to a publisher (2001’s unlamented Lifers), wrote two more before the tenth one caught the eye of my agent (though she didn’t sell it until ten years later, when it emerged as 2013’s Chum), then wrote six more before I sold my second novel, 2007’s The Electric Church. Since then, I’ve published six other novels—but also wrote ten that haven’t sold. The lesson here is simple: finishing a novel is a great achievement, and you should pat yourself on the back and have a celebratory cocktail if you manage it. Then you should get over yourself, because finishing a novel is the Participation Trophy of the writing world.

As A.M. Dellamonia, author of Child of a Hidden Sea, explained about writing her first salable novel: “I had been writing and submitting stories to short fiction markets from the time I was fourteen; I attempted my first complete novel when I was twenty-one, but naturally it wasn’t salable. There were perhaps two more unsalable novels after that, during the period when I started selling short stories and, in 1995, went to Clarion West. The sale came in 2007 so if I count back from that first attempt when I was fresh out of university … Yikes! Let’s go with a long time—more than a decade!”

So just how hard is it, on average, to become a published novelist with an advance and everything? Self-publishing is a more complex situation, of course; anyone can self-publish a novel these days with zero monetary investment, but the vast majority of self-published books sell less than 250 copies and earn very little money for their authors. That doesn’t mean that self-publishing isn’t worth pursuing, but self-publishing lacks some of the advantages of traditional publishing, like advances (which guarantee at least a minimum earning on the novel—of my nine published novels, only four have “earned out” the advance), marketing and promotion from professionals, and the distribution and sales teams. Getting the advance and the publishing contract isn’t easy, though—something that becomes obvious when you start looking at the numbers.

Authoring by The Numbers

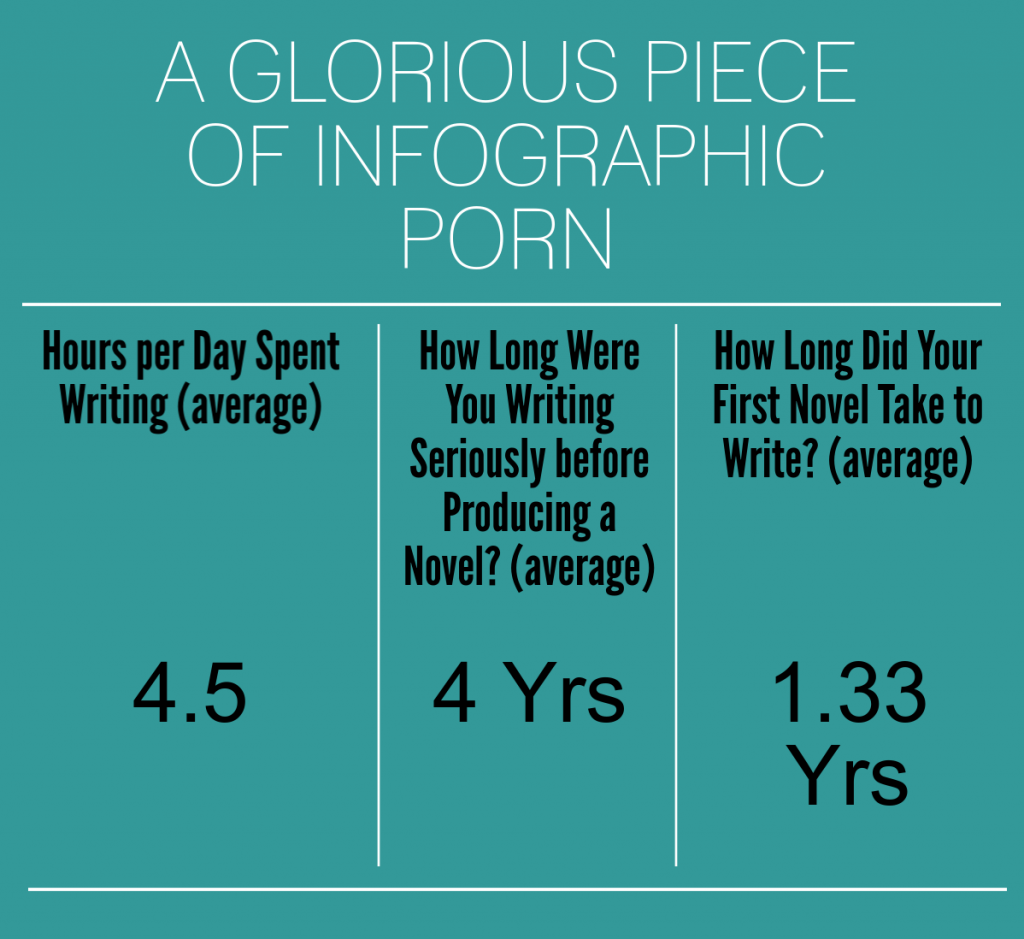

First and foremost, writing a novel that sells—whether we’re talking about a self-published or traditionally-published book—takes time and effort. A lot of time and effort. How much time and effort? Well, looking at a survey author Jim C. Hines conducted back in 2010, reaching out to authors personally, and doing some light reading on the Internet, we come up with nearly 300 data points that allow us to create this glorious piece of infographic porn:

There is, of course, a great range in these numbers. At least one author reported their first attempt at writing produced a novel, and other responses ranged from 5 weeks before producing a novel to five years—which, if you’re writing 4.5 hours a day, means they worked more than 8,000 hours before they had a mound of words that could be described as a novel—and one writer in the Hines survey reported they’d been writing professionally for 41 years before selling their first novel. Similarly, while 4.5 hours a day is the average for our professional novelists, the responses ranged from one hour spent writing per day to a whopping 14, which seems to leave little time for, well, anything else aside from basic survival.

Bill Cameron stressed the time factor for us: “I wrote Chasing Smoke in a coffee shop, and logged each writing session. I have 367 entries, and I always had one latte per session. (I finished the manuscript during a frenzied week long trip to a friend’s cabin which featured many pots of coffee, bottles of of beer, and tears, but I didn’t log any of that.)”

Ray Daniel (Corrupted Memory) gave his own numbers on how long it took to write that first novel—and how the discipline can pay off: “It took two years to write the first draft of my first novel. I rewrote it twice after that. The whole process took five years. I wrote two other novels in the next four years. Nine years after I started my first novel I got a three book deal for all three books.”

Many writers take advantage of situations where their schedules allow them to work almost nonstop, such as those with teaching jobs who have their summers free, or other scenarios. Kari Lynn Dell (The Long Ride Home) says she wrote her first novel in “One summer. That was back when I worked as a high school athletic trainer and had summer break but my husband didn’t, and we were still childless. I could write until my butt went numb whenever it suited me and I was too dumb to second guess every sentence so the words just poured out.”

And actually producing a novel that you think can sell is just step one. Most writers seeking traditional publication get an agent, as most of the major publishers still won’t look at unsolicited submissions—though there are exceptions. My own first novel was published by a tiny company, and I sold it without an agent—though, years later when they were out of business and I asked my agent to review the contract to ensure I didn’t have any worries, I came to wish I’d gotten the agent first. Agents aren’t just gatekeepers, they’re often sources of invaluable wisdom about both the artistic and the business side of publishing, and 77% of the respondents to the Hines survey and our own investigation had an agent when they sold their first novel.

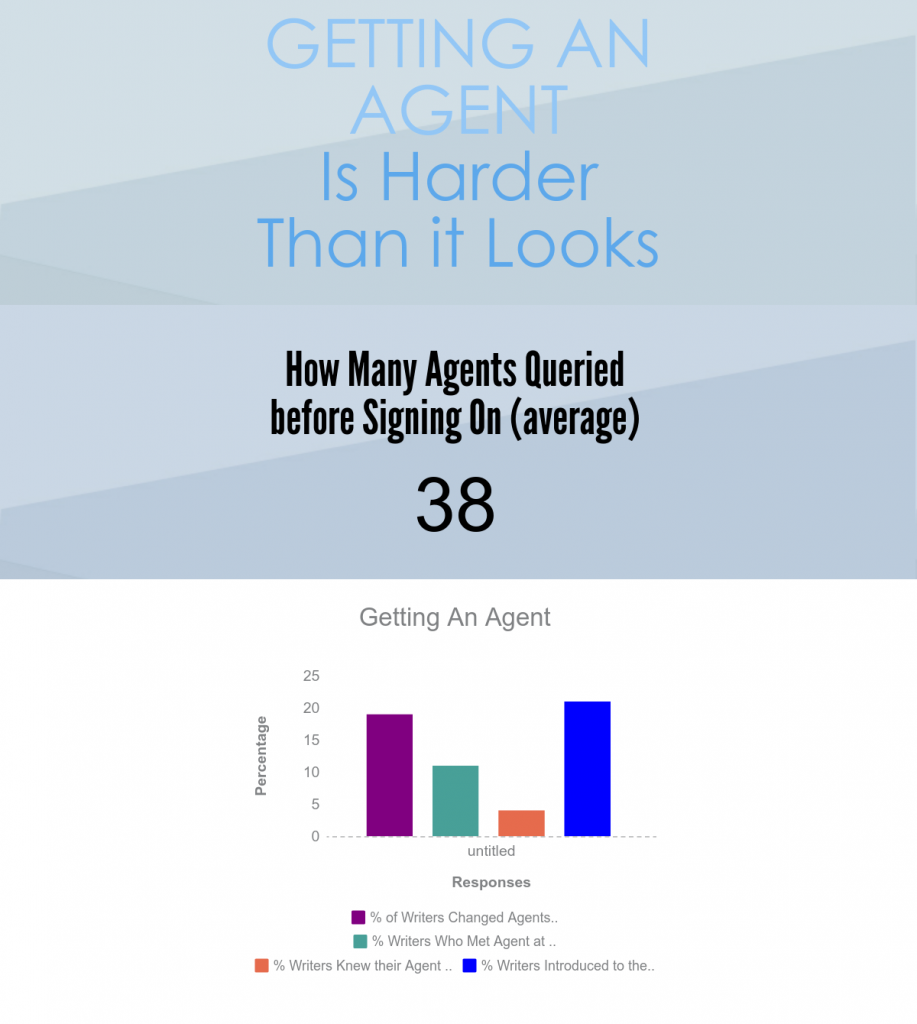

Getting an agent is often as much work as selling the book:

Looking at the numbers, getting an agent isn’t easy—the range on agents queries before hitting pay dirt goes from zero (meaning the author in question signed on with someone they already knew) to 200 queries, and a significant number of writers pursued agents doggedly not only by sending out queries, but by leveraging personal connections and networking and tirelessly attending conventions and events where agents were either taking pitches or participating in panels. I personally queried 24 agents before fooling my representative into taking me on, a feat I am still very proud of.

Author Gary Corby (Death Ex Machina) outlined his own “saga” in acquiring an agent (noting “I’m tolerably sure I made every error you can make in the query process.”): “Well, first I called every literary agent in Australia. All five of them. The conversation went like this, every time:

Phone rings

Agent: Hello?

Clueless Me: Hi, I’ve just written a novel and–

Agent: Are you previously published?

Clueless Me: No

Agent: Sorry, can’t help you.

“So then, to confirm I was doomed, I queried ten agents in the U.S. Four of them asked for the manuscript! I ended up signing with the excellent Janet Reid. That was a saga in itself, as in the interim I had managed to destroy both my email address and my web site.”

And even if you get an agent, there are no guarantees, as nearly 20% of the polled writers switched agents before selling their first novel. The reasons for switching were varied, of course, ranging from the agent literally disappearing, never to be heard from again, to changes in the genre the agency focused on, to simple traditional dissatisfaction with the handling of their career. The take-away is that selling a novel is a rough climb with a lot of stops along the way that can become permanent if you let them.

And even if you do get a high-powered agent who then secures the hallowed “six figure advance” for your novel, it still doesn’t mean you’re a shoe-in for literary legend, because sometimes things just go very, very wrong.

Filthy Lucre

Speaking of advances: if you’re selling a novel, as opposed to giving away a novel, you’re hoping to make some money from the deal. In the traditional publishing world the advance is still A Thing, and there are definite advantages to an advance. For one, the author gets paid even if the book doesn’t sell, which could be due to the book itself or due to marketing or distribution problems at the publisher. For another, it protects the author from the up-and-down business of books sales, which anyone who’s ever self-published a book will attest can be brutal.

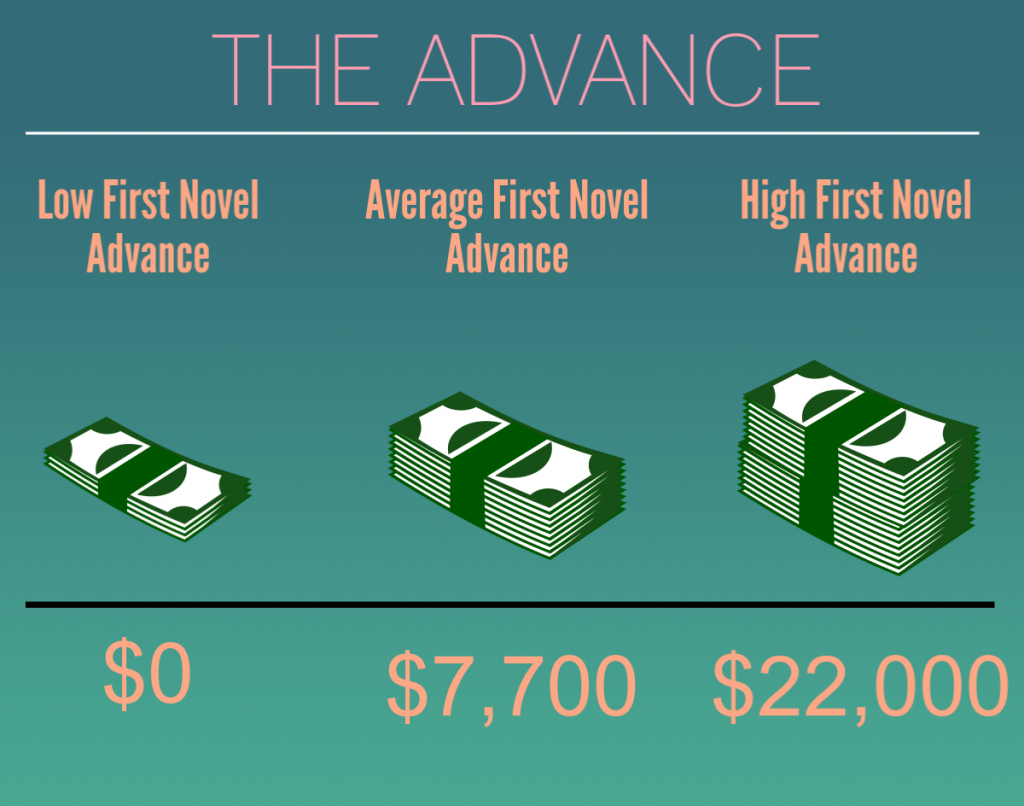

So, how much did people make? The average advance reported by our polled authors was $7,770, which is more or less right on target for the average reported by the industry for first-time novelists. The actual range starts at $0, which isn’t completely unusual for a small publisher, to $22,500. For myself, my first advance, sold without an agent, was $1,000. At the time it seemed like incredible money (this was in 1999; I was 28 years old, unmarried, and living in a tiny Jersey City apartment surviving on lite beer and Ramen, so $1,000 could be reasonably expected to last me several years), especially since I would soon be a bestseller. In the end, I actually received $545.00 in cash and the rest in copies of my own books (that is one long story, let me tell you), most of which I still have in boxes here.

It’s good to keep in mind that these are first-novel advances; assuming that first novels sells well, the next advance might be much more. Or, if the novel sells poorly, it might be much less, or nonexistent. And then there’s the middle between those two poles, where you sell enough to prompt another contract at the same basic advance, but never rise above it—which is not a bad place to be.

It’s also interesting to put it all together: on average, a writer sells their first novel for less than $8,000 after working 4.5 hours a day for 4 years. Assuming they worked five day work weeks and took two weeks vacation every year, that job pays $1.78 an hour. of course, if the book sells and royalties come in, the hourly wage on writing a novel can only go up.

The Intangibles

Writing is creative, and so it’s not possible to quantify everything that goes into a novel: the imagination, the ideas, the technique, the inspiration. But you can certainly try, so we asked our participating authors a few key questions about their writing process so aspiring authors can get a sense about things like professional behavior in the privacy of your writing cave, the influence of interaction with other living things on your writing, the effects of substances and ingestibles on the creative process, and the power of intangible powers that can’t always be quantified. In other words, we asked the following questions:

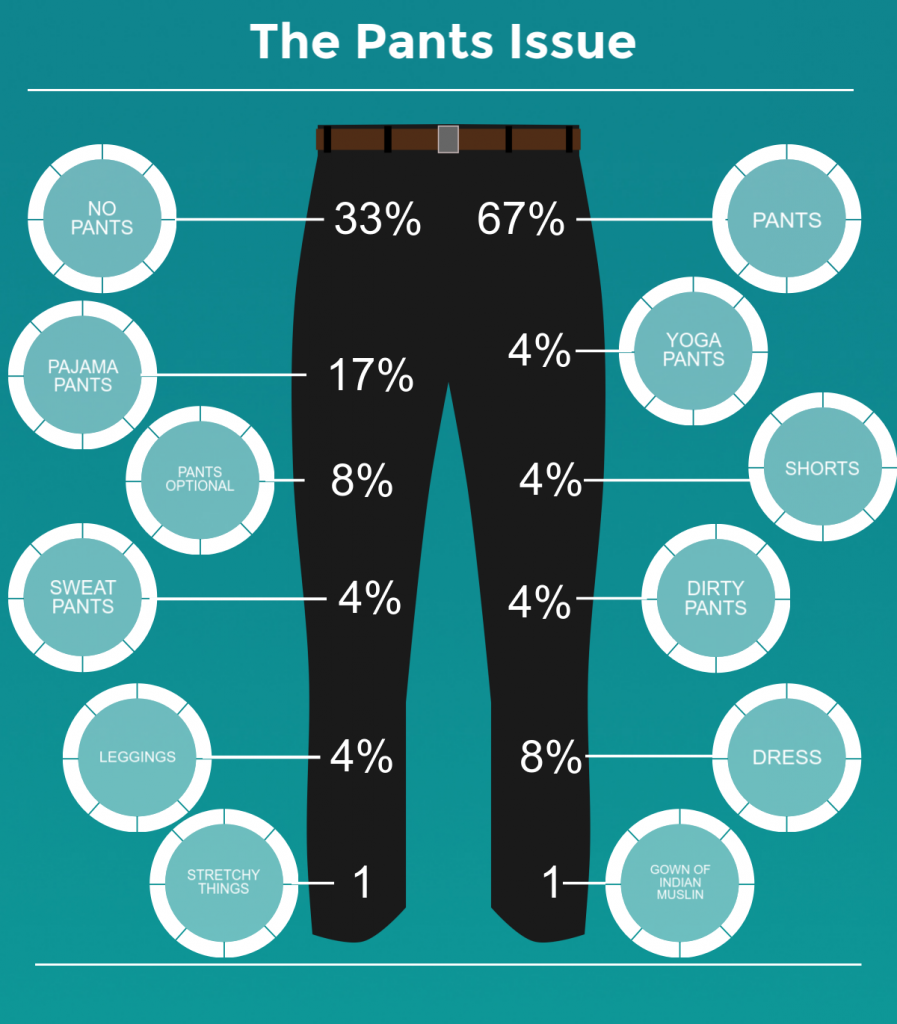

- Do you wear pants while writing?

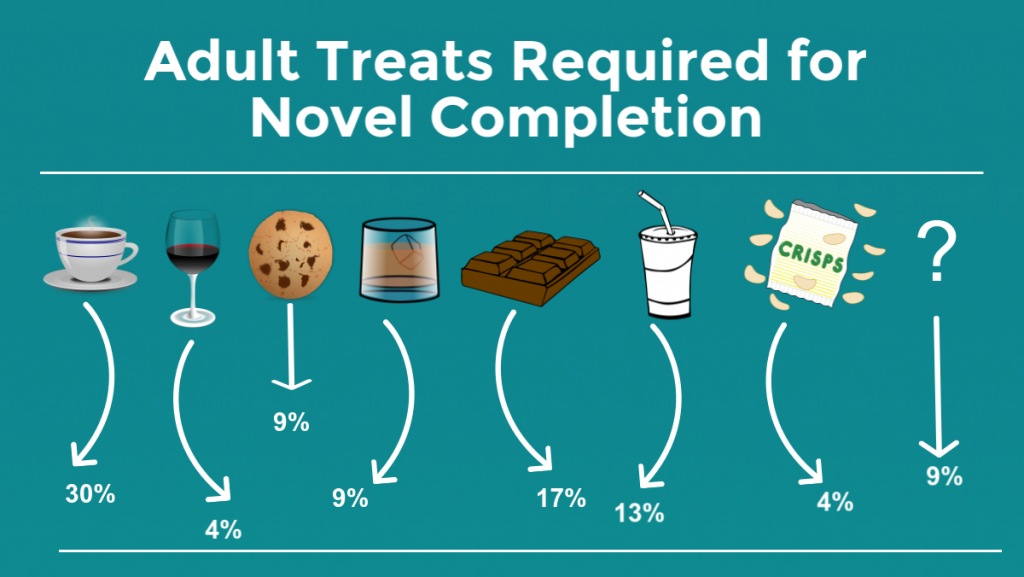

- How many cocktails/candy bars/cups of coffee does it take to write a novel?

- How many pets did you own while writing that first novel?

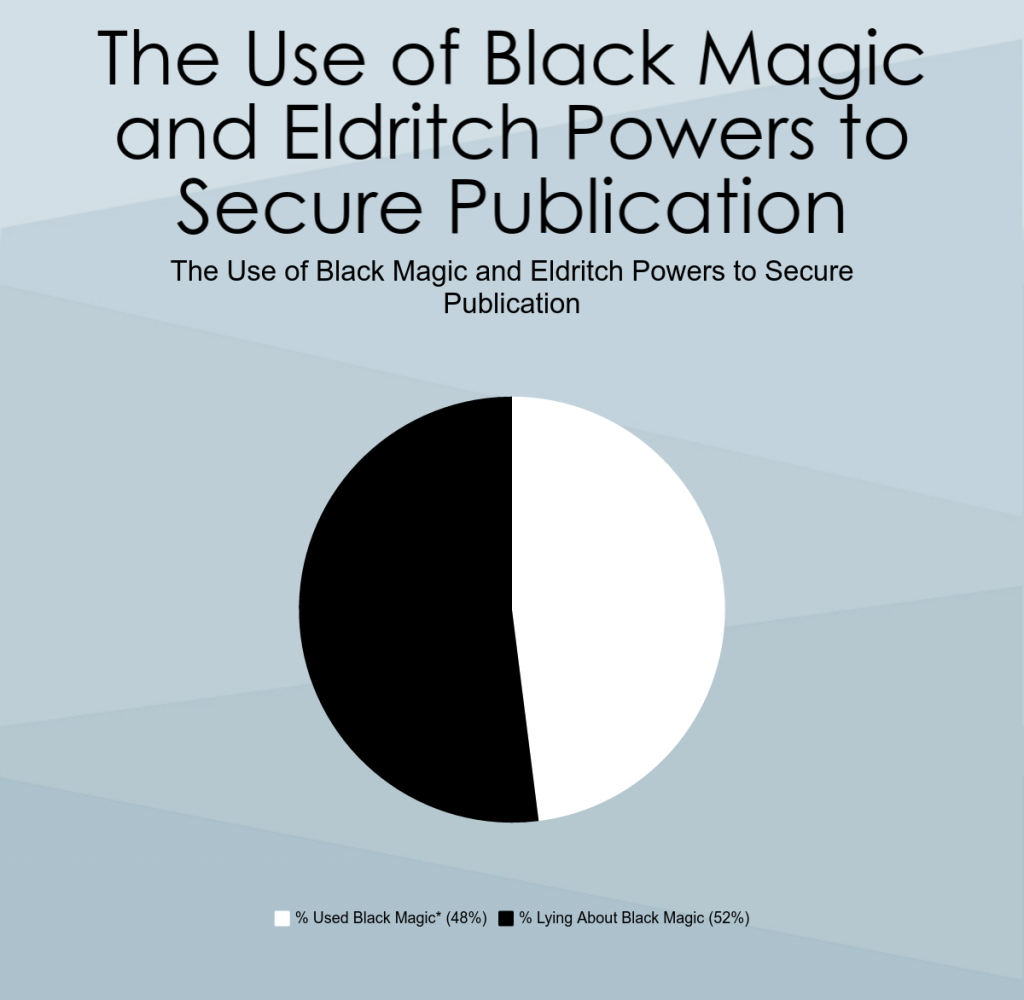

- Was any sort of black magic or eldritch power based on Old Gods involved?

The responses were illuminating:

The Pants Issue

Adult Treats Required for Novel Completion

Pets and Their Effect on Novel Writing

| # Pets Owned at Time of First Novel Sale* | Advance for Novel |

| 0 | No answer |

| 3 | $8,000.00 |

| 0 | $20,000.00 |

| 2 | $3,000.00 |

| 1 | $8,000.00 |

| 1 | $5,000.00 |

| 1 | $1,000.00 |

| many | $4,000.00 |

| 0 | $6,000.00 |

| 316 | $0.00 |

| 0 | $4,000.00 |

| 4 | $10,000.00 |

| 0 | $1,000.00 |

| 4 | $6,000.00 |

| 1 | $5,000.00 |

| N/A | $3,000.00 |

| 0 | No answer |

| 0 | $17,500.00 |

| 1 | $4,500.00 |

| 2 | $20,000.00 |

| 0 | $3,500.00 |

| 2 | $22,500.00 |

| 1 | $7,500.00 |

| 3 | $15,000.00 |

| 2 | $1,000.00 |

| 0 | $11,000.00 |

| 2 | No answer |

*Kari Lynn Dell wins this for all time by reporting she has “One dog, two feral barn cats, thirteen horses, and somewhere around 300 cows. I’m still angling for a goat, but my husband isn’t in favor. Spoilsport.” We are relieved at least she didn’t include the husband in her list of pets, as my own wife certainly would.

The Use of Black Magic and Eldritch Powers to Secure Publication

*Kari Lynn Dell again wins this one: “[I live on] the Blackfeet reservation. Hence, a smudging ceremony or two in our tipi, complete with burning sweetgrass and offerings of ceremonial tobacco.”

As you can see, most writers, disappointingly, wear pants while writing, and there is almost no correlation between pet ownership, alcohol, coffee, or snack consumption and writing success—although clearly everyone is sacrificing a chicken or two when submitting manuscripts—which kind of forces me to change the way I was going to end this essay. Believe me, the conclusion where we celebrated a future without pants, where writers were encouraged to own as many cats or dogs as possible while more or less being required to drink whiskey and eat chocolate was going to be epic.

Instead, let’s just conclude with: writing is work, just like any art form, and while it might seem like writers just bang out stories and cash checks, the time investment is pretty steep, even when accounting for differences in approach and lifestyle. The only thing that binds all of these authors together is this: all of them write for at least an hour every day.