Taking a Break from Butt-in-Chair

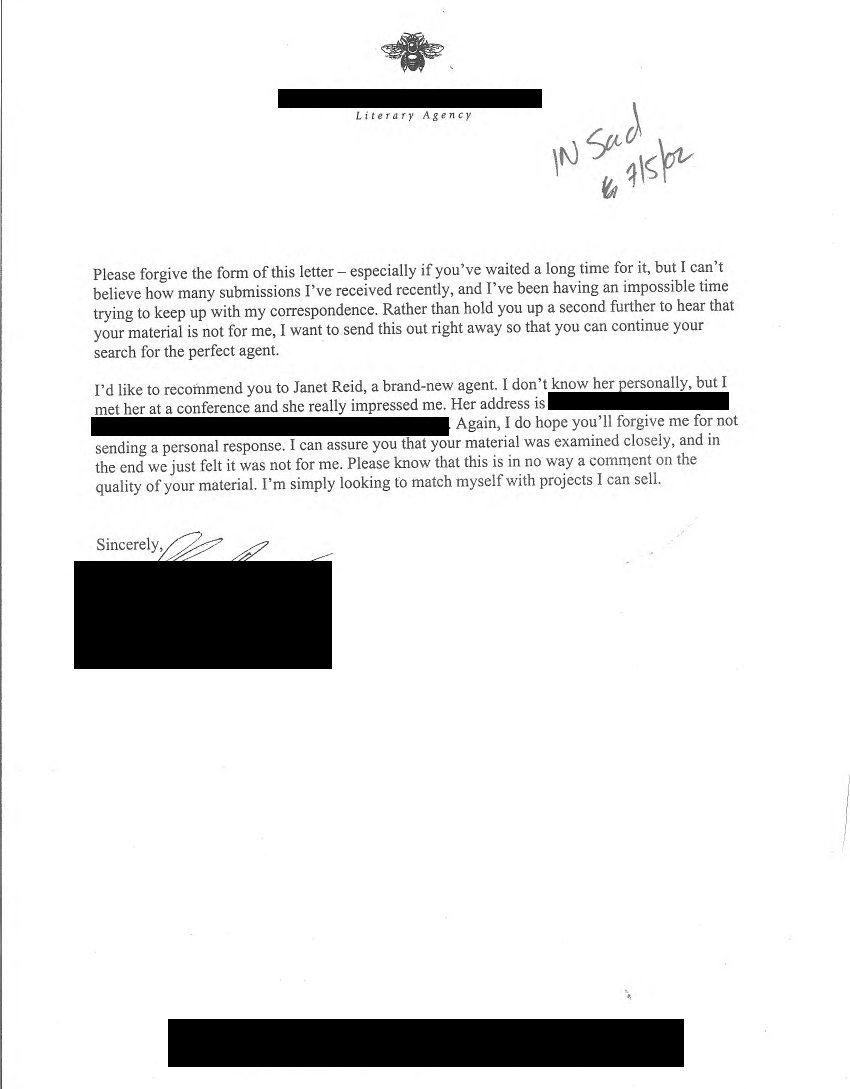

When you start talking about writing a novel, you’ll eventually hear a variation of the phrase “butt-in-chair.” This is generally pretty good advice: You can’t write a book if you don’t make yourself, you know, sit down in front of a keyboard and write it. So making sure you get (and keep) your butt in the chair for good long intervals is sound advice.

Like a lot of advice or best practices or rules, the whole point of learning them and understanding their benefits is so you can break them judiciously.

Take a Nap

I always refer to Mad Men when I discuss creativity, because one thing that TV show brilliantly handled was creativity. Don Draper is a writer, a creative guy. And the show goes out of its way to show Don goofing off—or, apparently goofing off. Don goes to the movies in the middle of the day. He drinks in his office. He naps. He goes home. You would be forgiven for asking what, precisely, Don does aside from wear the hell out of a suit and be charming.

The point is, Don’s creativity often resembles goofing off. Creativity needs discipline, so butt-in-chair works. But creativity is also chaos and anarchy, so sometimes when it’s just not happening you really do need to just get out of the chair. Take a walk. Take a nap. Drink a half bottle of cheap bourbon and go running through the neighborhood shouting about flat-earth theories. Whatever it takes.

The point is, you can’t take advice too literally. Butt-in-chair is a good rule of thumb, but it doesn’t mean you force yourself to sit there until you’ve written some arbitrary number of words. It just means you have to get into the habit of working or you’ll never actually work. It doesn’t mean the occasional half bottle of bourbon and arrest for public intoxication isn’t just as good for your soul.