The False Sense of Reality Security

There are a million ways to fail at world building and just a few ways to succeed. Creating a fictional universe from whole cloth without props, without visuals, actors, or any other crutches can be intimidating at best and maddening at worst.

Some writers retreat into scrupulous realism. No matter how fanciful their imagined universes are, they imagine that if they soak the text in facts, details, and thoughtful minutiae they will be insulated from any sort of Imaginary World Failure. They figure if they base every single aspect of their universe on something more or less “real”—something that actually happened, or is a naturally-occurring phenomena, no matter how rare, then no one can possibly find fault in their world-building.

Imagine this next part in the voice of Ron Howard: They can.

Fake It ’til You Make It

It’s frustrating, but sometimes fictional universes seem more realistic if you don’t bother getting into the nitty-gritty. Vaguebooking your world-building seems counter-intuitive, but it works, because it keeps things simple.

Look, world-building is tangentially-related to lying. You’re making something up. And the easiest way to make people suspect that you’re lying to them is to supply way too much detail. If you’ve ever gotten nervous when spinning a lie—to your parents, your teachers, your probation officers, or ex-wives—then you know that some point you just start babbling, throwing all sorts of supposedly confirming detail onto the bonfire of your dignity. And the more you talked, the worse it got.

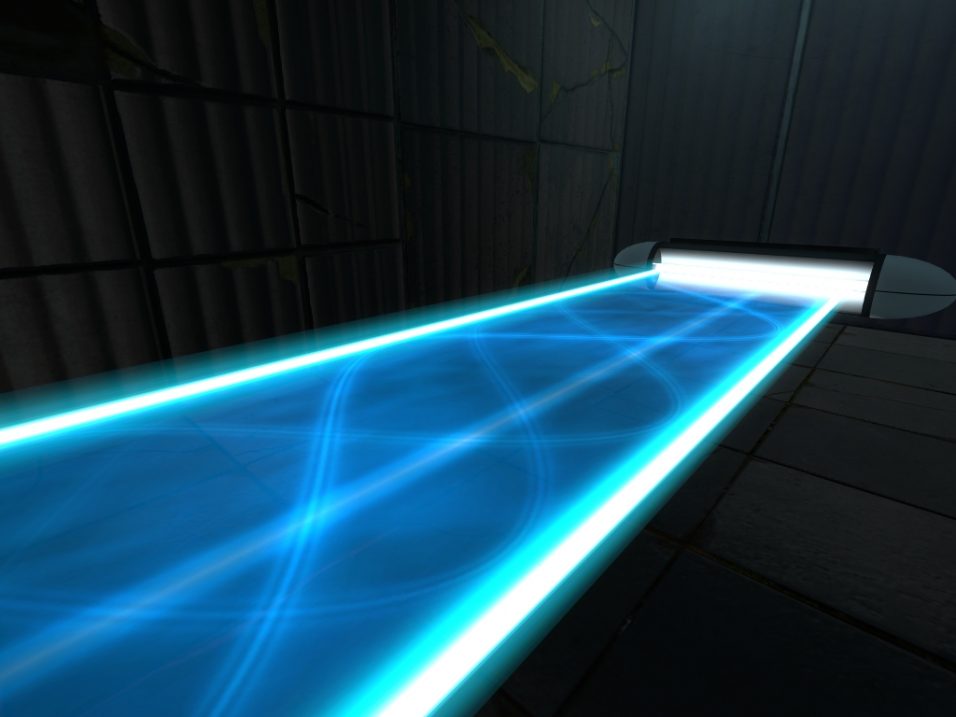

World-building can be like that. Tell someone that your futuristic society has developed hard-light technology that allows you to create structures out of pure light, and they go hmmn, sounds fancy. Start getting into pages and pages of explanations and equations and citations from real journals, and your reader starts to get a shifty look on their face as they slowly close the book and wonder what you’re really up to. Keeping it simple is usually better.

Unless you have actually created hard-light structures in your garage, in which case you are reading way the wrong blog.