The Han Solo Rule of Technology

Research continues to be the great bugbear of many writers’ lives. Writers in general trend to suffer from pretty severe Impostor Syndrome because we just sit around making shit up instead of doing literally anything else, and so there’s a certain sense that we have to become literal experts in anything we write about, so we can take on all comers when someone complains about the way we imagine space travel in our interstellar ice pirate epic.

This is tosh, of course. When writing sci-fi and dealing with speculative technology or science—even stuff based on real-world science—the key is similar to lying. As long as you believe it, you’re golden. In other words, look to Han Solo in Star Wars and worry less about scientific accuracy and more about sounding like it all makes sense.

The Spaces Between

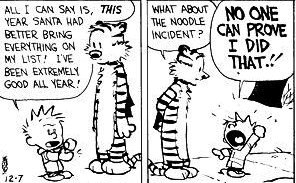

In the original Star Wars, if you recall, Han Solo brags that his ship the Millennium Falcon is the ship that did the “Kessel Run” in 12 parsecs. The Kessel Run is a great example of a Noodle Incident—a cool-sounding feat that is never actually explained. Why is the Kessel Run famous? Why is speed important? You can imagine answers to those questions, but you don’t have them.

Now, saying you did the Kessel Run in 12 Parsecs sounds pretty cool and impressive, especially when delivered with Harrison Ford’s trademark sarcastic charm. But it’s meaningless. A Parsec is a measurement of distance, not time, and it isn’t even very commonly used. So Han Solo dropped some grade-A gibberish on us.

(Note: Some super fans have twisted themselves into knots trying to argue that it actually does make sense, but these arguments are by and large kind of dumb.)

So, the lesson here is simple: Don’t sweat the science. Take a page from George Costanza from Seinfeld, who once famously advised that something is not a lie if you believe it to be true. Your science doesn’t have to make sense. It just has to sound good. Making it sound good is the challenge, here.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I have to go tend to my quantum particle fields.