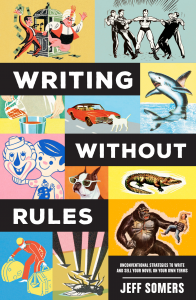

Reading for You

One of the best pieces of advice any writer can receive is the admonition to read constantly and widely. There’s no better writing class than the brilliant writers who have come before you—that’s not a revelation, it’s the sort of advice we all kind of know instinctively, I think.

The writing world can be a little insular. Once you start following agents and writers in Twitter and keeping up with all the spilled tea behind the publishing scenes, it gets a little echo-chambery, and part of that effect is the reading list. Every week there’s a new batch of book you’re “supposed” to read because it’s the new hot thing in literary circles, or because of its back-story, or simply because everyone on your feeds is talking about it.

You can’t go wrong reading anything, really, but sometimes you need to step back from the “must read” hot lists and read some book just because you want to.

Break Out

One of the most depressing things about life is that someday you will be gone, but people will continue to produce books, films, and other art. Yes, someday they will release a Star Wars movie and you will be dead, and thus unable to see it. And someday a novel that you would absolutely love will be released, and you will not be able to read it. Again, because in this scenario—in case it isn’t clear—you are dead.

Trying to keep up with the current hot takes in the literary world can be a bit exhausting, and it also means you’ll wind up reading a lot of books that just don’t do it for you. Nothing wrong with that; you can learn about your craft from any novel, good, bad, in your wheelhouse or so far out of it it’s not even in orbit around your wheelhouse.

But sometimes you need to feed your soul. Maybe that means taking a break to read some classics. Or some history. Or some trashy thrillers. Whatever your secret sauce, sometimes you have to put aside the new hotness out there and stop worrying about being able to jump into every single hashtag and just read for, you know, pleasure.

Me, I’m currently reading a history about restaurants in America. Will that ever be useful to me as research for my fiction, or teach me a better way to write a fight scene? Probably not. But damn, I’m enjoying it.