Lenses So Thick You Can See the Future!

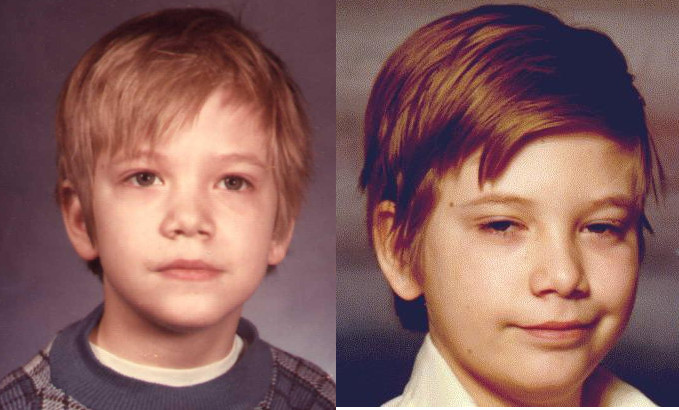

I’ve worn glasses since I was a wee lad. When I first got glasses, my father, bless his heart, was convinced I was going to suddenly become Babe Ruth on the Little League field, where up until that point I was a bit more Mario Mendoza. His childlike faith that glasses were going to transform me into a star athlete still warms me today. Ah, Dad, you fool.

So I’ve been wearing glasses for most of my life—in fact, I really can’t recall a time in my life when I could see clearly without them, a time when I didn’t wear glasses. I don’t recognize myself in mirrors without them, frankly. Contacts? Jebus, the thought of jamming something into my eye is terrifying. Plus also I am incompetent and there is absolutely zero doubt that I would wind up with contact lenses embedded in my brain.

Trust me.

The Price of Incompetence

I was initially told I needed glasses to see the board in class, and so I didn’t have to wear them all the time. Now these first glasses—let’s call them Lenses Mark One—were huge. I mean, huge. Like, they were twice the size of my face, and the lenses seemed thick enough to offer views of the future, or possibly to protect my eyes from laser attacks. Like, they were big.

And expensive, relatively speaking. By this point in my existence I think it’s fair to say I’d become much more expensive than either of my parents had ever imagined possible, and the glasses were just one more insult. I mean, I was nine years old and already breaking down physically. Where would it end? Very likely in an iron lung, or perhaps a plastic bubble costing millions of dollars.

Anyway, the glasses were huge and so I only wore them when necessary, furtively slipping them on when I absolutely had to glean some information from the blackboard. Otherwise they went into my shirt pocket, and it took me about six days to lose them.

I thought my mother was going to have a stroke. Another pair of glasses was procured, and my parents sat me down and offered a rundown of my relative value when compared to the glasses, which was not in my favor. So I started wearing my glasses all the time, in terror.

True Grit

This did solve the problem of my general incompetence as it intersected my glasses, and I did manage to never lose a pair of glasses again, because, as noted above, I can’t even imagine living without a pair on my face. However, true incompetence, such as the kind I enjoy, is never defeated. It is only temporarily stymied, and although it took twenty years I did manage to cost myself another pair.

I took it upon my self to do some repair work in my mother’s basement, working with some concrete and such. I’d just gotten new glasses, and twenty years of wearing them had burned in some behaviors. Friends used to mimic my patented three-part nervous habit of cleaning my glasses, off my baseball cap, and running a hand through my hair. I did this about five times an hour, so while I was working with cement and sweat and dust in my mother’s basement, wearing my new glasses, I cleaned them regularly … using my concrete-encrusted shirt. By the end of the day I couldn’t understand why my vision was so blurry.

As I forked over the money for a new pair, I thought I could hear my dear departed father chuckling somewhere, toasting his son, the idiot.

Sometimes it’s weird to think I’ll be wearing glasses for the rest of my life … but no one who comes across my bones will know. The good news is that since I’m convinced the rest of you are figments of my imagination who only exist to amuse me, all I need to do to make you all go away is take off my glasses. Problem solved.