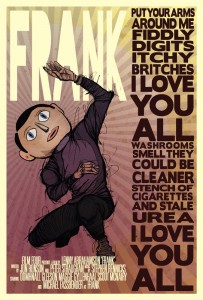

NOTE: The illustration included here was created by Ryan Gajda (http://www.sundaydogparade.com) and I neglected to credit him.

If you’ve heard of the film Frank, you’ve probably heard it described as the one where the improbably attractive actor Michael Fassbender wears a fiberglass head through 90% of the film or possibly as the one where this musician won’t take off his fiberglass head or somewhat less possibly as the one based loosely on the real-life Frank Sidebottom or something similar. And while that’s technically accurate description of the film Frank, both descriptions manage to miss the point, because this isn’t so much a movie about a crazy (and possibly genius) musician who wears a big round head all the time. It’s a movie about creativity, the creative process, and, most specifically, what happens when you want to be creative but aren’t very good at it.

We live in an age when every creative impulse (or desire for Kanye-style fame) can be indulged. Have a vague understanding of music theory and a desire to create songs? Grab GarageBand and go forth! Want to self-publish endless, turgid novels? Why not. Like photographing things? Here’s a camera in your pocket that also has an infinite number of automated filters to turn your dumb pics into processed dumb pics.

But just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. On the endless singing competition shows, there’s always a few dolts who whine on and on about how hard they’ve worked, how badly they want it. Which doesn’t fucking matter, because hard work and desire and the willingness to murder and eat babies in order to achieve success only counts if you can back it up with talent. So we’ve got a whole world out there convinced that just because they can (or think they can) recognize great art and appreciate great art and have a desire to create great art they can, therefore, create it. Which in 99% of these cases is absolutely not fucking true.

So: Frank.

The film opens with the main character, Jon, trying to find inspiration to write a song in his dull, routine day. He’s an aspiring musician, and in a few quick, smart bits we get the sense that he knows a bit about music, can put together a chord progression and a melody, has an interest in music history, and does the work. Sadly, and tellingly, the songs he comes up with are awful: The chord progressions are predictable crap, the lyrics are awful, and most of his songs don’t have any recognizable structure. They just meander aimlessly.

When Jon hooks up with Frank and his band, he finds himself out of his depth. Whether the music created for this film is actually good music or not can be debated, of course – but it is certainly more original and complex than anything Jon produces during the film. And that‘s the point. Frank’s mental illness and potential for musical genius isn’t the point – the point is that Jon does not have the creative spark required to produce anything of any value. And the film’s true story is about Jon’s attempt to glom onto the band’s more genuine skill and talent and somehow turn it into his own story of fame.

And fails. That’s the interesting thing: The point of Jon’s arc in this film is that he realizes, in the end, that he’d not a very good songwriter.

That’s pretty great. In lesser hands a story like Frank would be about how Frank, the troubled artist, breaks through and triumphs. Or it would be about how he and Jon learn from each other. Or it would be about Jon finding his inner muse, or suffering enough to produce something, or taking his experience with Frank and the others and turning it into an incredible piece of music. That would be more expected, and much less interesting.

The realization that you’re not good at something you’ve built your life around is perhaps the most painful thing any creative person can experience. The tantrums and tears on American Idol are real, usually, because these people have been self-deceiving for so long they can’t comprehend being told they don’t have “it”. Frank is the story of a guy who slowly comes to realize he doesn’t have “it”, and ruining several lives in his attempt to deny that fact.

Personally, I kind of enjoyed the strange music Frank and the band play during the movie. Fassbender is fantastic as Frank, who is a distinct character and personality despite wearing a fake head for 90% of the film, and is believable as an effortlessly creative and musical chap who is suffering from a seriously debilitating mental illness. But for anyone who aspires to creativity, be warned: This could be the most depressing movie you ever watch.

Blather, indeed, this post.

To equate success and talent, and to imply that hard work doesn’t matter in the least, is so blatantly untrue that it is laughable. Plenty of people achieve success – certainly commercial success – without a scrap of talent to their name and with very little in the way of hard work. Kanye is a good example. Keanu Reeves another. Stephanie Meyer a third. And the number of talented people who never catch a break – who put in the hard work and have the talent and never achieve “success” – is a not-so-small contingent. The most famous example is Van Gogh, who died destitute and unsung by any of the critics of the day, although there have been plenty. And I have seen many who lack less talent than some but work hard to make up for it and succeed as a result – Michael Jordan got cut from his high school basketball team, remember. In fact, it often seems as though those with the most talent don’t get far, because they don’t put in enough work to get good beyond their natural ability.

Success is an independent factor of talent and always has been; it is who you know, who is bankrolling you, and, occasionally, it is what luck you have. We do not live in a meritocracy, and never have, and to pretend that we do is absurd.

More than that, the idea that 99% of people shouldn’t even try simply because *you* don’t think they have potential is complete nonsense. Haven’t you ever taken philosophy 101, Jeff? The notions of “art” and “good art” are completely subjective, and dependent entirely on the attitudes of the day, and telling people to not even bother smacks more of a desire to discourage competition than it does some sort of enlightened perspective on artistic greatness.

Your personal insecurities are showing, Jeff, and it’s not a very flattering angle. You might want to take a page out of Gaiman’s book (http://www.uarts.edu/neil-gaiman-keynote-address-2012), in the future – because the thing about art is, the more people there are making it, the more people there are enjoying it, and the more love and money there is to go around – and the quicker you realize that, the happier you’ll be.

That was a very, very long comment.