Note: A version of this essay appeared in The Inner Swine Volume 4, Issue 2, circa 1998. I removed some meandering from the original essay but left in my juvenile abuse of dashes. You’re welcome. Also, 1998 was a hella long time ago and the Coen Brothers have released a lot of films since then, none of which factor into this essay.

Dislike and Disdain in the Films of the Coen Brothers

Dislike and Disdain in the Films of the Coen Brothers

The Coen brothers, writers/directors/producers of the films Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink, The Hudsucker Proxy, Fargo, and The Big Lebowski, are, without any doubt, two of the biggest Swines to ever gain national distribution of their films. Put simply, The Coen’s absolute dislike and disdain for their fellow human beings is almost a palpable story element in every one of their films. They hate us. They make no bones about hating us. And we love them for it.

“What Heart?”

Violence is a major component in each of the Coen Brothers’ films, both outwardly directed violence against another character and, somehow worse, inward violence inflicted against the self. The Coen Borthers create universes where life and the cozy conditions required to sustain it hang by the barest threads, and they remind their audience of the bizarre and often completely random way you can be gutted from stem to stern by their fellow human beings. The Coens put forth the firm belief that all humans are basically simmering time bombs of murderous intent, and if pushed far enough anyone can start shooting.

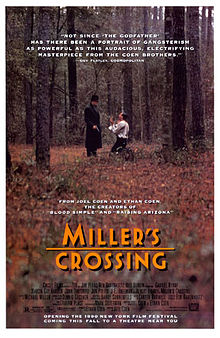

Miller’s Crossing is a perfect example of this theme. While all of their movies have a nerve-racking hint of senseless violence to them — Blood Simple revolves around a typical noir murder plot, Raising Arizona is a comedy about a baby kidnapped from its happy home and raised by escaped convicts, essentially, Barton Fink turns on the murder of a woman and the possibility that her head is encased in a box and carried around by the protagonist, The Hudsucker Proxy, which sports the least amount of outward violence of all their films, also sports three suicides, even if two of them fail, Fargo traces the downward spiral into animalistic homicide of several people, one of whom is presented to us as a normal guy with a family, and The Big Lebowski celebrates the joys of kidnaping, blackmail, property damage, and bullying with excited gusto — Miller’s Crossing beats them all due not only to the sheer number of murders and attempted murders, but in the main character’s complete inability to defend himself. Miller’s Crossing can be seen pretty easily as a lesson in man’s defenselessness against the violent whims of both nature and his fellow man.

Tom Regan, played with flinty Irish alcoholism by Gabriel Byrne, begins the film at the height of security: He is the number one right hand man of the local political boss of a vaguely defined city in a vaguely defined time period very much like the 1930s during prohibition. He is welcomed everywhere, powerful, well-liked, privileged because he has the trust and faith of the godfather of the Irish mob that runs the town. Then, through a plot which echoes any number of older crime novels from the period (most notably The Glass Key by Dashiel Hammet, which gives the Coens their plot, pretty much scene for scene) he loses it all: His security, his position, his personal safety.

During Tom’s fall and subsequent scramble to regain his security, the Coen’s remind us of the brutal randomness of life by beating the hell out of Tom on a regular basis. Tom takes a beating several times during the film, and each one is savage and, most importantly, completely unexpected. Tom gets hit as he walks out of rooms, after meeting with a rival boss, by his mistress, as he turns to exit a phone booth — each time he is knocked off his feet and loses his hat (Tom’s hat being a symbol of his personal power and control) and each time it is completely unexpected. He ends up nursing his new wounds and wondering where that one came from — never gaining any ability to predict these encounters. By the end of the movie Tom has put things right again — his boss is back on top and peace has come to the town. But Tom Regan walks away, realizing, after all those fists to his face, that not only will life fuck you over without a moment’s notice, but it is usually your fellow human being, your friend and lovers, who will be doing the screwing. The Coens delight in showing us how primitive and hair-trigger violent we all can be, if placed in the proper situation.

“Shut the Fuck Up, Donny!”

Akin to violence is the lack of sincere communication in the Coen Brothers’ movies. The characters within often use communication or a denial of it in a violent way, stupidly ignoring facts or advice or emotion and defending their own ignorance. The tone and insulting word choice of many Coen Brothers characters echoes the extreme violence, and underlines the belief that people are, in general, dumb animals constrained against violence by the barest of threads.

The dynamic between John Goodman’s character and the character of Donny in The Big Lebowski perfectly illustrates the Coens’ attitude toward people. Donny is an odd character, floating on the edges, never really a part of things, always trying to catch up on conversations he isn’t part of. John Goodman treats Donny with thinly-veiled violence, the phrase “Shut the fuck up, Donny!” is virtually all he says to him through the entire movie. Donny is constantly, pathetically, attempting to communicate and he is met with scorn, derision, and insults delivered in a tone of voice and level of volume usually associated with an enemy -and yet these characters are presented as friends, with supposed emotional ties to each other. That John Goodman’s character handles argumentative or combative situations by drawing a loaded gun and threatening his fellows is also telling.

The Coen Brothers present us worlds in which no one really listens to each other, in which petty differences can mushroom into murderous violence without warning. The communication barriers are plain and painful. Witness Fargo’s car salesman, plotting to have his wife kidnapped in order to make a small profit and ease his financial burdens, sitting on the phone with the loan officer requesting paperwork to prove that the cars they loaned money on were really bought. William H. Macy smiles, doodles nervously, and speaks in circles, forcing polite cheer in the place of sense and lucidity. The car salesman speaks, says nothing, and no one can understand him. After his own animal rises up and inadvertently causes the death of not only his wife and father-in-law but two other people as well, its no surprise in a Coen Brothers universe that he ends up howling inarticulately, like a beast, as he arrested in a nameless motel room.

People talk in Coen Brothers movies, but nobody really listens.

“You know, for kids!”

The final insult we, as their audience, take when we watch a Coen Brothers movie is the proclamation that our desires, usually small and petty to begin with, will amount to nothing. The implication found in all these films is that even our most wretched hopes and plans will be ruined by either our own stupidity or by the immense and purposeless violence intended for us for no reason by our fellows. Their films are filled with characters who not only fail to achieve whatever modest goals they have set for themselves, but who usually cause immense disaster due directly to their insipid and futile attempts to make a change.

Consider: The couple in Raising Arizona simply want a family, but their warped attempts to create a family cause nothing but suffering and chaos. The idiotic hero of The Hudsucker Proxy does manage to make himself famous and rich momentarily, but in the end his pursuit of his goals leaves him a broken man jumping out of a window. In Fargo, the car salesman’s minor dream of paying off his illicit debts results in a bloodbath and his own ruin. In The Big Lebowski, the main character simply wishes to have a ruined rug replaced. This minor goal, and his apathetic efforts towards it, result in a mess that indirectly kills one of his friends. The Coens paint everyone not only as prisoners of violence and our primal, dumb urges, but as futile prisoners: everything we idiots try, they seem to be saying, is doomed. And will probably get all our friends killed.

The basic tenets of a Coen Brothers film are these:

1) people are dumb and do not listen to anything they do not already agree with.

2) People are inherently violent and are capable of incredible crimes with very little motivation.

3) Life can easily be upset and ruined by random acts of such violence, against which we have no defense.

4) Thus, all of our hopes and dreams are doomed, only we’re too dumb to realize it, and if we do attain some minor and short-lived success, we’re too dim to prepare for the ruin about to rain down upon us. They really do hate us.

So, in short, the Coen Brothers view their fellow humans as stupid, violent, sad people who will never get what they want. It’s an honest opinion, and one we tend to share. People are stupid. People are senselessly violent. People usually do fail in their attempts to attain anything greater than themselves. The Coen Brothers don’t dress sup their hatred of their fellows with any false sentiment or ludicrous faith; they know we’re all pigs, and they’re not afraid to say so.